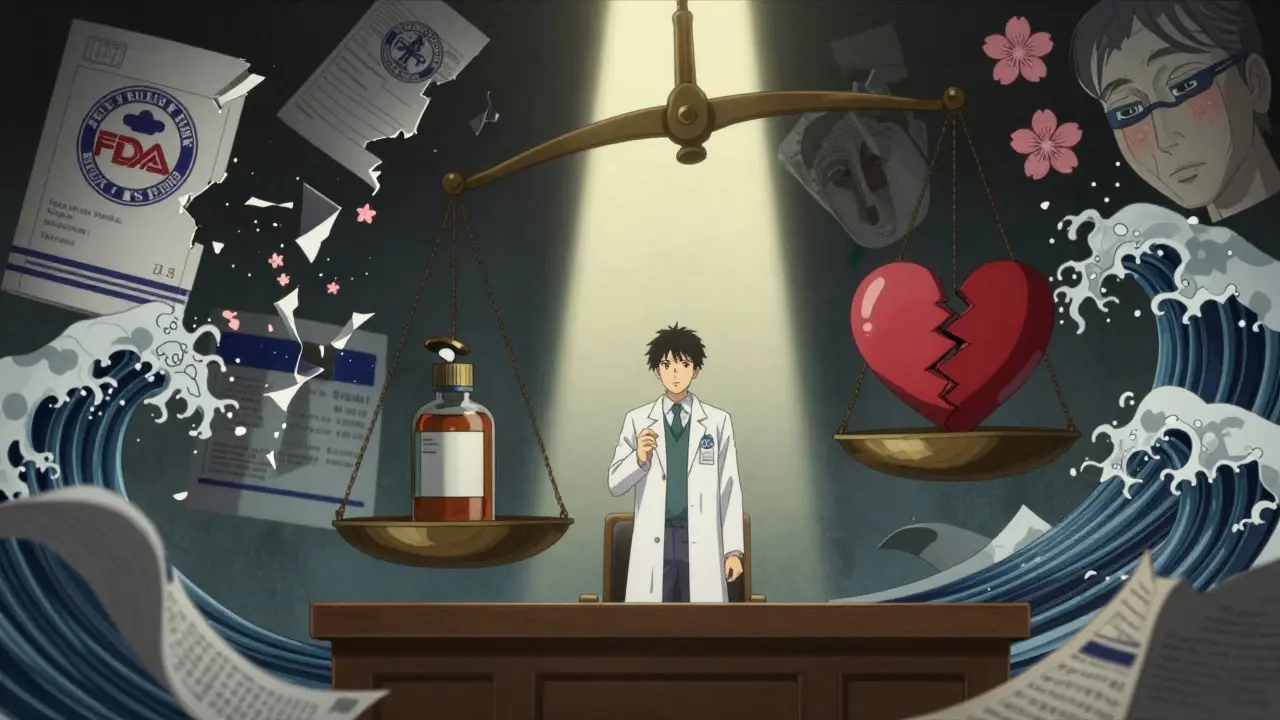

Every time a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic, they’re making a decision that could carry legal weight. It’s not just about saving money-it’s about whether that switch could lead to harm, lawsuits, or even permanent damage to a patient’s health. In 2026, with generics making up over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., this isn’t a rare edge case. It’s daily practice. And the legal landscape hasn’t kept up.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t as Simple as It Looks

Generic drugs are supposed to be identical to brand-name versions. The FDA says they must be bioequivalent-meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream within the same time frame. That sounds solid. But bioequivalence doesn’t mean therapeutic equivalence, especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI). These are medications where even a tiny change in blood levels can cause serious harm. Think of drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or antiepileptics. For warfarin, a 10% shift in absorption can mean the difference between a clot and a stroke. For levothyroxine, a slight drop in hormone levels can trigger fatigue, weight gain, depression-even heart problems. And for epilepsy patients, a switch in generic formulations has been linked to a 7.9% increase in seizure risk, according to the American Epilepsy Society. The problem? Two patients could get the same generic drug from the same pharmacy, but if it came from different manufacturers or batches, their blood levels might vary enough to cause clinical consequences. And because generics aren’t tracked by batch number in most systems, there’s no way to trace which version caused the issue.The Legal Trap: Who’s Responsible When Something Goes Wrong?

Here’s where it gets messy. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing that generic drug manufacturers can’t be sued for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to use the exact same label as the brand-name drug. They can’t change it, even if new safety data emerges. That means if a patient has a bad reaction and the label didn’t warn about it, the manufacturer can’t be held liable under state law. That leaves patients with nowhere to turn. And pharmacists? They’re caught in the middle. In 27 states, pharmacists are protected from greater liability when they substitute a generic. But in 23 states-including Connecticut and Massachusetts-there’s no such protection. In those places, if a patient is harmed after a substitution, the pharmacist could be sued for negligence, even if they followed the law. And here’s the kicker: patients often don’t know they’ve been switched. A 2021 Patient Advocacy Foundation survey found 41% of patients didn’t realize their prescription had been changed until they started feeling worse. Pharmacists aren’t always required to tell them. In 18 states, there’s no mandatory patient notification beyond the package insert.State Laws Are a Patchwork-And That’s Dangerous

You can’t treat this like a national issue. It’s 50 different systems. One state might require patient consent before substitution. Another might mandate substitution unless the doctor says “do not substitute.” Some states require pharmacists to log every substitution with batch numbers. Others don’t track anything at all. The results? States with strong protections and clear notification rules-like California, Texas, and Florida-have 32% fewer malpractice claims tied to substitution, according to the National Community Pharmacists Association. States without those safeguards? 27% more claims. Take Connecticut. No liability protection. No mandatory patient notification. A 2019 case ended in a $3.2 million verdict against a pharmacist after a patient suffered neurological damage from an antiepileptic substitution. The court couldn’t hold the manufacturer liable due to federal preemption. The pharmacist was the only one left standing.What Pharmacists Can Do Right Now

You can’t change federal law. But you can control how you practice. Here’s what works:- Know your state’s laws-and check them every year. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy updates its compendium annually. Don’t rely on memory.

- Use EHR alerts-set up your electronic health record to flag NTI drugs. If a prescription is for levothyroxine, valproate, or cyclosporine, the system should pause and ask: “Is substitution approved?”

- Document consent-even if your state doesn’t require it, use a simple form. “I understand this prescription has been switched from [brand] to [generic]. I’ve been told the risks.” Have the patient initial it. It’s not a guarantee, but it’s proof you tried.

- Communicate with prescribers-if you’re unsure, call the doctor. Many physicians don’t realize how risky substitution can be for NTI drugs. A quick conversation can prevent a disaster.

- Track batches-start logging generic drug batch numbers, even if it’s just in a notebook. If a patient reports an issue, you’ll have data to trace back.

- Get supplemental insurance-standard malpractice policies often exclude substitution-related claims. Look for coverage that specifically includes generic dispensing risk.

When to Say No

There are times when substitution isn’t just risky-it’s irresponsible. For NTI drugs, many pharmacists already refuse substitutions, even when the law allows it. A 2022 survey of 452 pharmacists found 74% have declined a substitution for an antiepileptic, thyroid, or blood thinner because they felt the risk was too high. You’re not overstepping. You’re doing your job. The American Medical Association’s 2021 policy explicitly supports requiring patient consent for NTI substitutions. And patients? They’re not mad when you explain why. In fact, 87% of pharmacists say patients appreciate the extra caution, according to the National Association of Chain Drug Stores.

The Bigger Picture: Is the System Broken?

The cost savings from generics are real. Between 2009 and 2018, they saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.67 trillion. That’s life-changing for millions. But at what cost? The current system creates a legal black hole. Manufacturers can’t be sued. Pharmacists are exposed. Prescribers are often unaware. Patients are uninformed. And when something goes wrong, no one takes responsibility. New proposals are emerging. The 2023 “Generic Drug Safety Act,” introduced in 11 states, would require generic manufacturers to update labels within 60 days of new safety data-something they’re currently barred from doing. A pilot program by the FDA has already processed over 200 label change requests, though generics initiated only 12% of them. A more promising idea? “Consensus labeling.” Instead of 1,278 different manufacturers using 1,278 slightly different labels, a single, standardized label-updated by a neutral body-would be used by all. This would eliminate the preemption problem and give patients consistent warnings. Five states are already piloting this under the Interstate Pharmacy Compact.What’s Next for Pharmacists?

You’re on the front line. You’re the last person to check the prescription before it goes to the patient. That means you’re also the last line of defense. Start small. Pick one NTI drug-maybe levothyroxine-and implement a checklist for it. Talk to your prescribers. Educate your staff. Document everything. Don’t wait for a lawsuit to force you to act. The system isn’t perfect. But you can make your corner of it safer. And that’s not just good practice-it’s professional responsibility.Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes, in 23 U.S. states, pharmacists can be held liable for harm caused by generic substitution if their state doesn’t provide legal protection. Even if the substitution followed state law, a patient can still sue for negligence-especially if the drug has a narrow therapeutic index and the pharmacist didn’t document consent or notify the patient.

Are generic drugs always safe to substitute?

No. While generics are bioequivalent for most drugs, they’re not always therapeutically equivalent for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and antiepileptics. Studies show a 7.9% to 18.3% increase in adverse events after substitution for these medications, even when the FDA approves them as equivalent.

What are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs?

NTI drugs are medications where small changes in blood concentration can lead to serious harm or therapeutic failure. Examples include warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), phenytoin and carbamazepine (antiepileptics), and cyclosporine (immunosuppressant). For these, even a 10% difference in absorption can be dangerous.

Do I have to tell patients when I substitute a generic?

It depends on your state. In 18 states, pharmacists are legally required to notify patients directly-not just rely on the package insert. In the other 32, notification isn’t required. But even in states without a law, best practice is to inform patients, especially for NTI drugs. Patient surveys show 41% didn’t know they were switched until they had side effects.

Can I refuse to substitute a generic even if the law allows it?

Yes. Pharmacists have the professional right-and often the ethical duty-to refuse substitution if they believe it poses a risk to patient safety. Many do this for NTI drugs. The American Medical Association supports requiring patient consent for these substitutions, and 74% of pharmacists surveyed in 2022 reported refusing substitutions for high-risk drugs despite legal permission.

How can I protect myself legally?

Use a 7-step risk-reduction protocol: (1) Know your state’s substitution laws, (2) Set EHR alerts for NTI drugs, (3) Get documented patient consent, (4) Communicate with prescribers, (5) Log batch numbers, (6) Complete an annual liability risk assessment, and (7) Get supplemental malpractice insurance that covers substitution risks. These steps reduce liability exposure and show you acted with due diligence.

Eric Gebeke

18 Jan, 2026

Let’s be real-pharmacists are the new scapegoats for a broken system. Manufacturers get immunity, doctors don’t know what’s going on, and patients blame the person handing them the pill. Meanwhile, the FDA lets 1,278 different labels exist for the same drug. This isn’t negligence-it’s systemic abandonment. And now you want me to log batch numbers like I’m running a warehouse? I’m not a supply chain manager, I’m a clinician. This is a federal failure, not a pharmacy failure.

Joni O

19 Jan, 2026

Y’all need to stop treating this like a legal minefield and start treating it like patient care. 😊 I started using EHR alerts for NTI drugs last year-game changer. Even just adding a checkbox: ‘Patient informed?’-it changes the whole vibe. Patients appreciate when you care enough to pause. One guy told me, ‘I thought my meds were broken, but you actually listened.’ That’s why we do this. Small steps, big impact. 💪

Andrew McLarren

19 Jan, 2026

It is imperative to acknowledge the profound structural deficiencies inherent in the current regulatory framework governing generic pharmaceutical substitution. The doctrine of federal preemption, as established in PLIVA v. Mensing, creates an untenable legal vacuum wherein accountability is systematically displaced from manufacturers to frontline practitioners. This constitutes a de facto privatization of risk, wherein the burden of administrative diligence and clinical judgment is externalized onto pharmacists without commensurate legal or financial protections. A harmonized, nationally standardized labeling protocol, administered by an independent, evidence-based body, would constitute a necessary and ethically defensible reform. Until such time, pharmacists are being asked to serve as de facto risk managers in an environment where the rules of engagement are neither transparent nor equitable.

Robert Cassidy

20 Jan, 2026

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART. Big Pharma owns Congress. The FDA is a joke. They let some Chinese factory pump out 17 different versions of levothyroxine and call them ‘equivalent.’ Then they tell the pharmacist: ‘You’re on the hook if someone dies.’ Meanwhile, the CEO of Teva is on a yacht in the Mediterranean sipping champagne. We’re not talking about a pill-we’re talking about a government-sanctioned murder machine. And you want me to ‘document consent’? What’s next? A waiver for chemotherapy? This isn’t healthcare. It’s corporate feudalism.

Dayanara Villafuerte

21 Jan, 2026

Y’all are acting like this is a new problem. 😒 I’ve been doing this since 2010. The first time a patient came in crying because her seizures came back after a ‘generic switch’? Yeah. I called the prescriber. I logged the batch. I made her sign a form. And I still got called ‘a bad pharmacist’ by the insurance rep. 🤦♀️ Bottom line: If you’re not tracking batches and getting consent for NTI drugs, you’re playing Russian roulette with a loaded gun. And no, your malpractice policy won’t save you. Get the add-on. Do it. Now. 🚨

Andrew Qu

23 Jan, 2026

One thing I’ve learned: the best defense is a good paper trail. I started keeping a simple logbook-drug name, batch #, patient initials, date. No fancy software. Just a notebook. And I tell every patient: ‘This is the same medicine, but it’s from a different company. Some people feel different on it. Let me know if something changes.’ Most say ‘thanks for telling me.’ That’s it. No drama. No lawsuit. Just human communication. You don’t need a law degree to do this-you just need to care enough to ask.

Danny Gray

25 Jan, 2026

Let me ask you something-if generics are truly bioequivalent, why do we even have this debate? It’s like saying two identical twins have different personalities. Either the science is wrong, or the FDA is lying. Or maybe… the whole concept of ‘bioequivalence’ is a corporate myth designed to justify cost-cutting? I’ve seen patients on the same generic, same dose, same pharmacy, and one gets sick while the other doesn’t. That’s not pharmacology. That’s chaos theory. And we’re pretending we can control it with checklists? Wake up.

Tyler Myers

26 Jan, 2026

They’re hiding something. The FDA won’t let manufacturers change labels because they’re scared of lawsuits. But the real reason? They’re in bed with Big Pharma. The brand-name companies pay the FDA to keep generics locked in. That’s why batch tracking isn’t mandatory-it’s a cover-up. If you could trace which batch caused the seizure, you’d know it’s the same factory in India that made the tainted heparin in 2008. They don’t want you to know. And they sure as hell don’t want you to connect the dots. This isn’t incompetence. It’s a cover-up. And you’re all just signing forms while the system burns.