When a pregnant person takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in their body. It crosses over to the baby. This isn’t magic. It’s biology. And it’s more complex than most people realize. The placenta isn’t a wall. It’s not a filter that blocks everything bad. It’s a dynamic, living organ that lets some things through-and keeps others out-based on chemistry, timing, and even the baby’s stage of development.

It’s Not a Barrier. It’s a Gatekeeper.

For decades, doctors assumed the placenta protected the fetus like a shield. That changed in the 1950s and 60s with thalidomide. Thousands of babies were born with severe limb defects because their mothers took this drug for morning sickness. The placenta didn’t stop it. It carried it right through. That tragedy forced medicine to rethink everything. Today, we know the placenta is selective. It weighs about half a kilogram, is roughly the size of a dinner plate, and has a surface area of 15 square meters-enough to handle all the nutrients, oxygen, and yes, drugs, moving between mother and baby. But not everything crosses equally. Some drugs slip through easily. Others barely make it.What Makes a Drug Cross?

Four main factors decide whether a drug gets to the baby: size, solubility, charge, and protein binding. Size matters. Drugs under 500 daltons (Da) cross more easily. Ethanol, at 46 Da, zips through. Nicotine, at 162 Da, follows right behind. But insulin? At 5,808 Da, it barely makes a dent. Less than 0.1% of the mother’s insulin reaches the baby. Lipid solubility. Fats love to cross membranes. If a drug is oily (log P > 2), it slips through the placental cells like butter on toast. That’s why drugs like methadone and buprenorphine cross so well-over 60% of the mother’s dose ends up in the baby. Charge. At body temperature (pH 7.4), drugs that are ionized (charged) struggle. Think of it like trying to push a magnet through a wall-opposite poles repel. A drug that’s fully charged at this pH might see its transfer drop by 80-90%. Protein binding. Most drugs in the blood stick to proteins like albumin. Only the unbound portion can cross. Warfarin? 99% bound. So even though it’s small and oily, almost nothing gets to the baby.The Placenta Has Its Own Security System

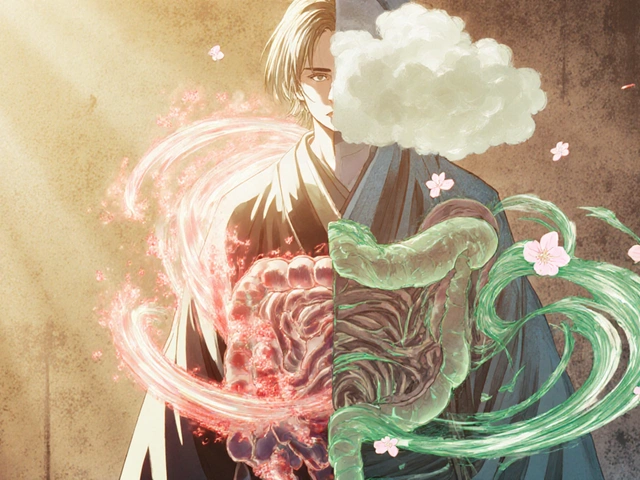

It’s not just passive. The placenta has built-in pumps-transporters-that actively push drugs back toward the mother. Two big ones: P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). These aren’t just bystanders. They’re gatekeepers. When researchers blocked P-gp in lab models, HIV drugs like saquinavir and lopinavir jumped 2-3 times higher in fetal blood. That’s huge. It means the placenta was actively fighting to keep them out. Even more telling: the cord-to-maternal blood ratio. For lopinavir, it’s 0.6. That means the baby’s blood has only 60% of the mother’s concentration. For zidovudine? 0.95. Why? Because zidovudine uses a different transport system that doesn’t get blocked by P-gp. And it gets smarter. The placenta doesn’t just pump drugs out-it can change how much it pumps based on the drug. Methadone and morphine don’t just cross. They block the pumps that move other drugs like paclitaxel. That’s competition at the cellular level.

Timing Changes Everything

The placenta isn’t the same at 8 weeks as it is at 38 weeks. In the first trimester, the barrier is looser. Tight junctions between cells aren’t fully formed. Efflux pumps like P-gp are still developing. That means drugs cross more easily early on. That’s why timing matters more than we think. A drug that’s safe at 28 weeks might be risky at 8 weeks. Many birth defects happen in the first 12 weeks, when organs are forming. Yet most studies use placentas from full-term births. That’s like studying a car’s brakes by only testing them after the trip is over. Experts like Dr. Carolyn Coyne point out the gap: we’re missing critical data on early pregnancy. We don’t know enough about how drugs behave when the baby’s heart, brain, or limbs are forming. That’s a blind spot.Real-World Examples: What Crosses-and What Doesn’t

Let’s look at real drugs and what we know:- SSRIs (like sertraline): Cord-to-maternal ratio of 0.8-1.0. Nearly equal. About 30% of babies exposed show temporary jitteriness, feeding issues, or mild breathing trouble after birth-called neonatal adaptation syndrome.

- Methadone: Fetal levels at 65-75% of maternal. Leads to neonatal abstinence syndrome in 60-80% of newborns. Withdrawal starts within hours after birth.

- Valproic acid: Crosses easily. Cord ratio near 1.0. Linked to 10-11% risk of major birth defects-like spina bifida or cleft palate-compared to 2-3% in the general population.

- Phenobarbital: Also crosses well. Used for seizures. Babies can be sleepy at birth but usually recover.

- Digoxin: Surprisingly, it crosses without much trouble. Even when you give the mother drugs like verapamil (which block P-gp), digoxin levels in the baby don’t change. Why? Because it doesn’t rely on P-gp. It uses a different path.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

One in three pregnant people takes at least one prescription drug. One in four takes two or more. Yet 45% of prescription drugs still lack clear safety data for pregnancy. The FDA now requires placental transfer data for new drugs. That’s progress. But the system is still catching up. Many drugs used for depression, epilepsy, pain, or even high blood pressure were approved before we understood how deeply the placenta influences fetal exposure. We’re starting to fix this. The NIH’s Human Placenta Project is using radioactive tracers to watch drug movement in real time. Placenta-on-a-chip models are now 92% accurate at predicting what happens in real human tissue. And companies are pouring money into this-funding jumped from $12.5 million in 2015 to nearly $48 million in 2022. But there’s a dark side. Nanotech is being explored to deliver drugs directly to the fetus. Sounds promising. But nanoparticles might get stuck in the placenta. We don’t know the long-term effects. The same tools that could one day cure fetal disease might also cause harm if we don’t understand the balance.What Should You Do?

If you’re pregnant and taking medication:- Don’t stop cold turkey. Some conditions (like epilepsy or depression) are more dangerous to the fetus than the drug.

- Work with your OB-GYN and pharmacist. Ask: "What’s the cord-to-maternal ratio for this drug?" and "Is there a safer alternative?"

- For drugs with narrow safety windows (like digoxin or lithium), ask about therapeutic drug monitoring. Blood tests can help keep levels safe for both of you.

- Remember: the first trimester is the most sensitive. If you’re planning pregnancy, review your meds now-not after you find out you’re pregnant.

The placenta doesn’t act alone. It responds to stress, infection, even the mother’s diet. It’s alive. It adapts. And it’s not always predictable. That’s why blanket statements like "it’s safe" or "it’s dangerous" don’t work. The answer is always: It depends.

Understanding how drugs cross isn’t just science. It’s about giving every pregnant person the tools to make informed choices-not fear-driven ones.

Can all medications cross the placenta?

No. Not all medications cross. Small, lipid-soluble, uncharged drugs (like alcohol, nicotine, and many antidepressants) cross easily. Large molecules (like insulin), highly protein-bound drugs (like warfarin), and those actively pumped back by placental transporters (like some HIV drugs) cross poorly or not at all. The placenta filters, not blocks.

Is it safe to take antidepressants during pregnancy?

For many women, yes. SSRIs like sertraline cross the placenta but have been studied extensively. The risk of untreated depression-like poor nutrition, preterm birth, or postpartum complications-often outweighs the small risk of temporary newborn symptoms. Decisions should be made with a doctor, weighing risks of the illness versus the medication.

Why do some drugs affect the fetus more than others?

It’s about chemistry and timing. Small, fat-soluble drugs cross faster. Drugs that bind to placental transporters like P-gp get pushed back. And early pregnancy is riskier because the placenta’s protective pumps aren’t fully developed. A drug that’s safe at 30 weeks might be dangerous at 10 weeks.

Do over-the-counter drugs cross the placenta too?

Yes. Acetaminophen crosses easily. Ibuprofen crosses well in early pregnancy but may affect fetal kidney function later on. Even herbal supplements like ginger or chamomile can cross. Just because something is "natural" or "over-the-counter" doesn’t mean it’s safe for the baby.

How do doctors decide if a drug is safe in pregnancy?

They look at animal studies, human data from registries (like the MotherToBaby database), and placental transfer models. The FDA now requires placental transfer data for new drugs. But for older drugs, doctors rely on decades of clinical observation and expert guidelines from groups like ACOG. There’s no perfect system-just the best available evidence.

Write a comment