The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) runs one of the most transparent systems in the world for tracking drug side effects. If you’ve ever wondered how regulators know if a new medication might be causing unexpected harm, the answer lies in the FAERS database - the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. This isn’t a secret archive. It’s public. And anyone can use it - researchers, patients, journalists, even curious citizens. But using it well? That’s where things get tricky.

What Is FAERS, Really?

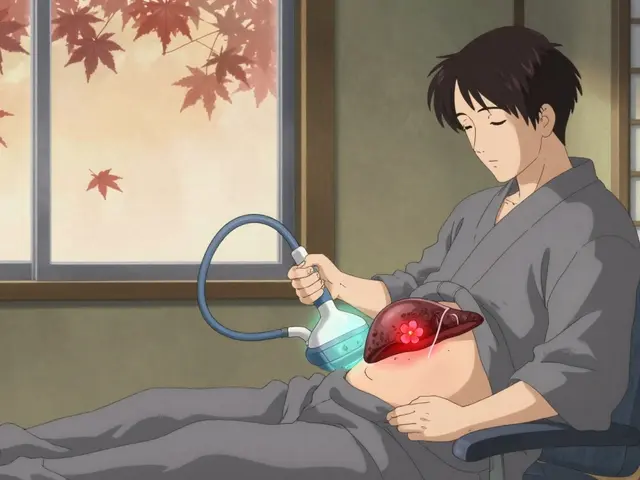

FAERS stands for FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. It’s been collecting reports of bad reactions to drugs and biologics since 1969. Today, it holds over 30 million reports, with about 2 million added every year. These aren’t lab results or clinical trial data. They’re real-world stories: a patient who had a stroke after taking a new blood pressure pill, a nurse who developed liver damage after a vaccine, a parent whose child had a seizure after starting a new ADHD medication.

These reports come from two main sources. About 75% are submitted by drug manufacturers - they’re legally required to report any adverse event they learn about. The other 25% come directly from doctors, pharmacists, and patients through the MedWatch program. Each report includes basic info: age, gender, what drug was taken, what happened, and when. The adverse events are coded using a standardized medical language called MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities). Without this system, comparing a headache reported by one person to a migraine reported by another would be impossible.

How Do You Access the Data?

The FDA gives you three main ways to dig into this data - each suited for different users.

- The FAERS Public Dashboard: This is the easiest entry point. No login, no code, no training. Just go to the FDA website, pick a drug, select an adverse event (like "heart attack" or "rash"), and see how many reports show up over time. It’s perfect for spotting trends - like whether reports of a certain side effect spiked after a new warning was issued. The dashboard lets you filter by age, gender, and year. It’s designed for non-experts.

- Quarterly Data Extracts: If you need raw numbers, the FDA releases downloadable files every three months. These are huge - sometimes 5GB - and come in ASCII or XML format. You’ll need software like R or Python to open them. This is where academic researchers and data scientists work. But be warned: the files are messy. Missing fields, inconsistent formatting, and duplicate entries are common.

- The OpenFDA API: This is the developer’s tool. It lets you pull FAERS data directly into your own applications using JSON. Want to build a tool that alerts doctors when a patient’s medication has recently shown a spike in liver injury reports? This API makes it possible. It’s free, well-documented, and updated quarterly. But it’s not user-friendly unless you know how to write code.

What’s the Catch?

Just because the data is public doesn’t mean it’s perfect. Experts warn that FAERS data alone can’t prove a drug caused an adverse event. Here’s why:

- No denominator: The database tells you how many people reported a side effect - but not how many people took the drug. If 100 people report nausea after taking Drug X, but 10 million people took it, that’s not alarming. If only 100 people took it? That’s a red flag. FAERS doesn’t give you the total number of users.

- Reporting bias: Serious events get reported more often. If a patient dies, it’s likely reported. If they get a mild rash, they might not. Healthcare workers report more often than patients. And manufacturers report only what they’re legally required to - sometimes missing details.

- Missing or inconsistent data: A 2021 study in Nature Medicine found that about 30% of reports lack complete information. One report might say "patient had chest pain"; another says "cardiac discomfort." MedDRA tries to standardize this, but human error still creeps in.

- No causality: The FDA’s own dashboard says it plainly: "FAERS data by themselves are not an indicator of the safety profile of the drug." A report of kidney failure after taking a new antidepressant doesn’t mean the drug caused it. Maybe the patient had pre-existing kidney disease. Maybe they were taking five other medications. FAERS flags patterns - it doesn’t prove cause.

Who Uses This Data - And Why?

Academics use FAERS to find rare side effects missed in clinical trials. A 2022 study at Johns Hopkins used FAERS to uncover a dangerous interaction between a common diabetes drug and an antidepressant that affected 1 in 10,000 users. That’s the kind of signal you’d never catch in a trial of 5,000 people.

Pharmaceutical companies rely on FAERS daily. All top 50 global drugmakers use it - but most don’t access it directly. Instead, they use commercial platforms like Oracle Argus Safety or ArisGlobal LifeSphere, which pull in FAERS data along with other sources and apply advanced algorithms to detect signals faster.

Patient advocacy groups use it too. In 2022, a nonprofit used FAERS to identify a pattern of severe allergic reactions to a widely prescribed asthma inhaler. Their findings helped push the FDA to update the drug’s warning label.

But here’s the gap: most users struggle with the learning curve. A 2023 survey by the International Society of Pharmacovigilance found that people need 40 to 60 hours of training just to understand MedDRA coding. The dashboard helps, but it’s like giving someone a car without teaching them how to drive.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA is making moves. In January 2024, they switched to the ICH E2B(R3) standard for electronic submissions. This means more detailed data - like exact dosing times and lab values - is now being collected. It’s a step toward better analysis.

By late 2024, the FDA plans to release a new API that lets developers pull live analytics from the Public Dashboard. And by Q3 2025, they’re adding natural language processing to help users search reports using plain language - like typing "my grandma had a stroke after taking this pill" instead of hunting through MedDRA codes.

The long-term goal? Integration. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is already testing ways to link FAERS data with electronic health records and insurance claims. That could finally solve the "denominator problem" - knowing how many people took a drug, not just how many reported a problem.

Getting Started: What You Need to Know

If you’re a researcher, start with the Public Dashboard. Spend an hour exploring. Type in your drug of interest. Look at trends over time. Compare it to similar drugs. Don’t jump to conclusions - just get a feel for the data.

If you’re a data analyst, download the latest quarterly extract. Use Python’s pandas library to clean the data. Filter out incomplete reports. Group similar MedDRA terms. Look for clusters - like whether a certain side effect appears more often in older women.

If you’re a patient or caregiver, don’t use FAERS to make health decisions. Use it to ask better questions. If you see a lot of reports about a side effect you’re worried about, bring it up with your doctor. Say: "I saw a pattern in the FDA’s database - should we talk about this?"

And if you’re frustrated by how hard it is to use? You’re not alone. The FDA admits the system is clunky. But it’s the best public tool we have. And it’s getting better - slowly.

Can I report an adverse event myself?

Yes. Anyone can report an adverse event through the FDA’s MedWatch program. Go to the FDA’s website, find the MedWatch form, and fill it out. You don’t need to be a doctor. Even if you’re unsure whether the drug caused the problem, report it. The more reports, the better the FDA can spot patterns.

Is FAERS the only drug safety database in the U.S.?

No, but it’s the main one. The FDA also uses the Sentinel Initiative, which links to insurance and electronic health record databases to track drug safety in real time. But Sentinel data isn’t public. FAERS is the only system that lets anyone see individual case reports.

Why don’t I see my drug in the FAERS dashboard?

If your drug is new, it might not have enough reports yet. The dashboard only shows drugs with at least 100 reports. Older drugs with millions of users, like aspirin or metformin, will have thousands. If your drug has very few reports, it doesn’t mean it’s safe - it just means few people have reported issues.

Can FAERS data be used in court?

FAERS data has been used as evidence in lawsuits, but courts treat it carefully. Judges know it doesn’t prove causation. It can show a pattern, but experts must testify that the pattern is meaningful. It’s a starting point - not a verdict.

How often is the data updated?

The FDA releases new data every three months - in March, June, September, and December. The Public Dashboard updates at the same time. If you’re doing research, always note which quarter’s data you’re using. Comparing data from different release cycles can lead to misleading conclusions.

Sarah B

7 Feb, 2026

FAERS is just another government database that looks good on paper but crashes when you actually try to use it. No denominator? Seriously? That's like giving you a car with no gas gauge. I report my side effects every time and I know I'm one of the few who actually bother. The system's broken and they don't care.

Heather Burrows

8 Feb, 2026

It's ironic that we have this massive archive of human suffering from pharmaceuticals and yet we treat it like a spreadsheet to be mined rather than a moral ledger to be honored. The real tragedy isn't the missing data-it's that we've normalized this level of systemic indifference.

Savannah Edwards

8 Feb, 2026

I've spent hours digging through FAERS after my mom had a reaction to her new blood pressure med. It's overwhelming but also kind of beautiful in a way-thousands of people, scattered across the country, all writing down their pain in little boxes so someone, someday, might notice. The data's messy, yeah, but it's real. I wish more people understood that. The FDA's not perfect, but they're the only ones trying to listen. I'm not a scientist, but I know what it feels like to be ignored. This database? It's the opposite of that.

Gouris Patnaik

9 Feb, 2026

America thinks transparency means dumping data online and calling it a day. In India, we don't have FAERS, but we have something better: community. When someone has a bad reaction, they tell their neighbors, their pharmacy, their doctor-verbally, face to face. No API needed. The real safety net isn't code-it's connection. Why are we so obsessed with digitizing suffering instead of humanizing it?

AMIT JINDAL

9 Feb, 2026

LOL the FDA wants us to use openFDA API? bro i tried to parse that XML file and my laptop cried. i just want to know if my migraine med is gonna kill me not learn python. also why is every report missing the dose?? like i took 10mg not 100mg but they just say "drug x"?? 🤦♂️

Amit Jain

10 Feb, 2026

You call this transparency? This is performative bureaucracy. The FDA releases data but makes it harder to use than a locked vault. Meanwhile, pharma companies have AI tools that predict side effects before the FDA even sees the reports. This isn't about public access-it's about control. And guess who gets left out? The people who actually take the drugs. Wake up.

Eric Knobelspiesse

10 Feb, 2026

i just tried to use the dashboard and it said no results for my med. then i checked the quarterly extract and found 87 reports. turns out the dashboard only shows ones with 100+ entries. so if you're one of the first 99? you're invisible. this isn't transparency. it's data censorship with a smiley face.

Jesse Lord

11 Feb, 2026

For anyone feeling overwhelmed by FAERS-start small. Pick one drug you care about. Look at the trend over 5 years. Compare it to a similar drug. You don't need to understand MedDRA to see if something's spiking. And if you see a pattern? Talk to your doctor. That's all this is meant for-not to diagnose, not to panic, but to start a conversation. You're not alone in finding this confusing.

Lakisha Sarbah

12 Feb, 2026

I reported my son's seizure after his new ADHD med. It took 3 days to fill out the form. No one called. No one followed up. I just hope it went somewhere. I don't need a dashboard. I just need someone to say 'we saw that' and mean it.

Ariel Edmisten

14 Feb, 2026

Just use the dashboard. Pick a drug. Look at the graph. If the line goes up after a new warning? That's a signal. No math needed. You don't need to be a coder to see a trend. Just pay attention.

Mayank Dobhal

14 Feb, 2026

I checked FAERS after my aunt had liver damage on a vaccine. Found 12 reports. 12. Out of 10 million doses. That's not a problem. That's a miracle. Stop scaring people with noise. The system works. It's not perfect. But it's not broken either.

Ashley Hutchins

14 Feb, 2026

Why are we even talking about this? The real issue is that the FDA lets drug companies delay reporting for months. And they get away with it. I reported my reaction in 2022. It only showed up in the 2023 data. That's a whole year of people getting hurt because the system is designed to protect corporations not patients. Wake up. This isn't transparency. It's a trap.