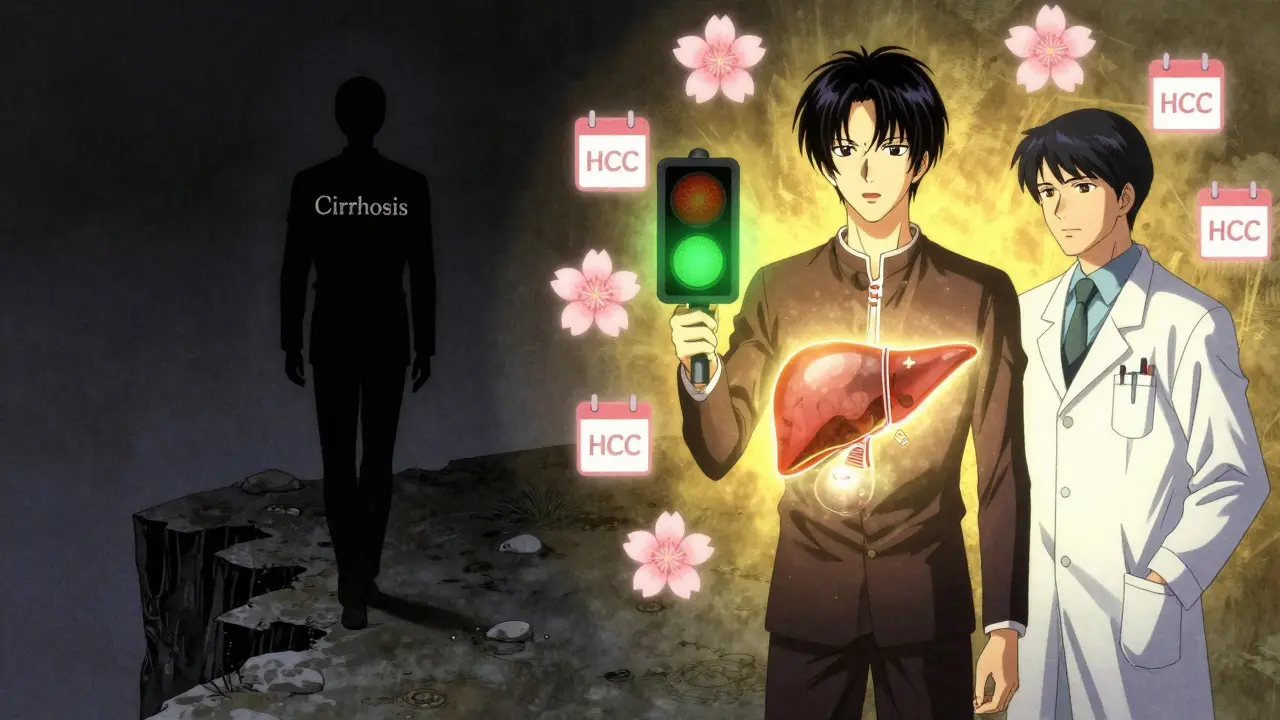

When your liver is scarred from cirrhosis, your risk of developing liver cancer doesn’t just go up-it skyrockets. About 80% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases happen in people who already have advanced liver scarring. That’s not a small chance. It’s the rule. And here’s the critical part: if you catch HCC early, your odds of survival jump from less than 20% to over 60%. The difference between living and not living often comes down to one thing-regular screening.

Why Surveillance Matters for People with Cirrhosis

Most people with cirrhosis don’t feel sick until it’s too late. By the time symptoms like belly pain, jaundice, or unexplained weight loss show up, the cancer is often advanced. That’s why waiting for symptoms is like waiting for a car crash before putting on a seatbelt. Surveillance isn’t about finding cancer early-it’s about finding it before it becomes life-threatening.

Studies show that people who get screened every six months with an ultrasound have a 50-70% five-year survival rate. Those who don’t? Only 10-20%. That’s not a slight improvement. That’s a life-or-death gap. The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to give you control. If a tumor is under 2 cm and hasn’t spread, you might still be eligible for a cure.

What the Guidelines Say: Ultrasound Every Six Months

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), and other major groups all agree on one thing: if you have cirrhosis, you need an ultrasound every six months. No exceptions. Not for hepatitis B. Not for alcohol-related damage. Not for fatty liver disease. If your liver is scarred, you’re at risk.

The science behind the six-month interval is simple: HCC tumors grow about 1-2 cm in that time. Screen too rarely, and you miss the window. Screen too often, and you waste money and cause unnecessary stress. Six months is the sweet spot. It’s based on real data from thousands of patients tracked over years.

Some guidelines also suggest checking a blood marker called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). But here’s the catch: AFP isn’t reliable. It can be high in people with no cancer, and normal in people who do have cancer. That’s why it’s only a conditional add-on. If your AFP is above 20 ng/mL, then you get further testing. If it’s normal? You still need the ultrasound.

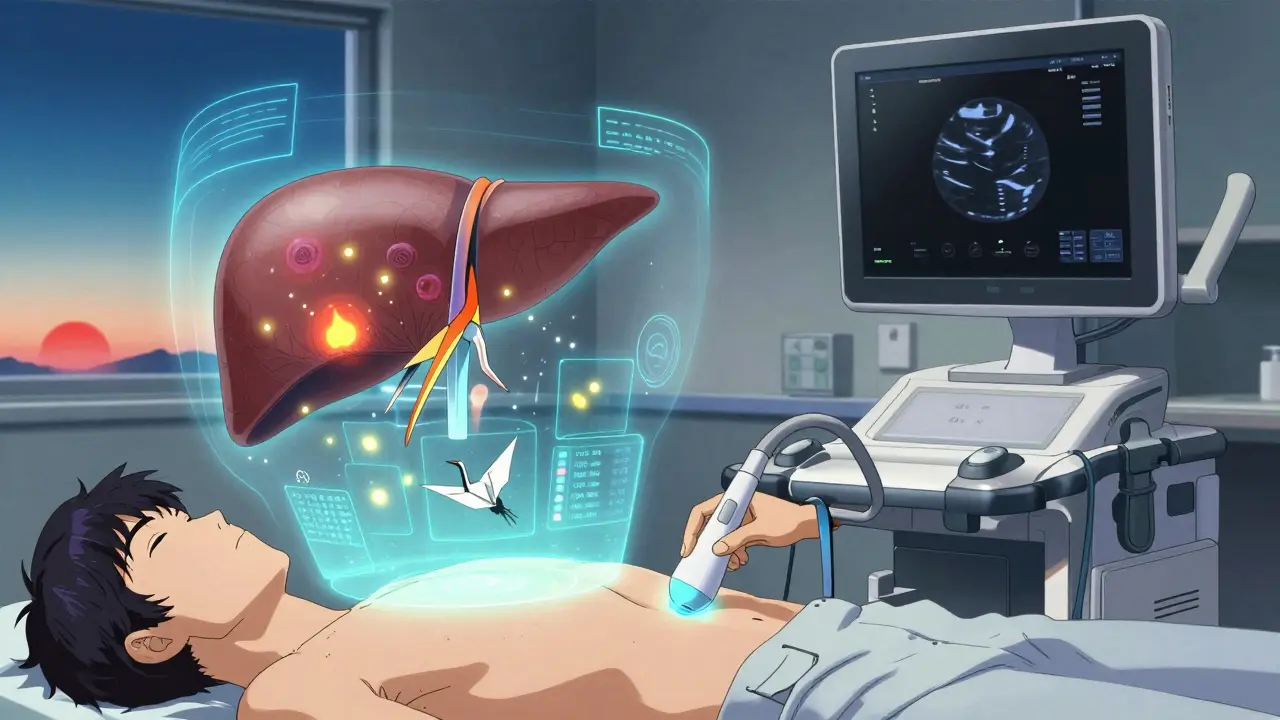

What Happens If Something Shows Up?

Let’s say your ultrasound finds a spot. What now? First, don’t panic. Not every spot is cancer. But you can’t ignore it. The next step is always a contrast-enhanced scan-either a CT or MRI. These use dye to show how blood flows through the liver, which helps doctors tell if a mass is cancerous.

The system they use to interpret these scans is called LI-RADS. It’s like a traffic light for liver tumors: green means likely benign, yellow means uncertain, red means likely HCC. The system works because it’s standardized. A radiologist in Sydney, Adelaide, or San Francisco will use the same language. Since its 2022 update, agreement between doctors has jumped from 45% to 78%. That’s huge.

If the scan confirms HCC, your treatment path depends on how far it’s gone. Most screen-detected tumors are still at Stage 0 or A-the earliest. That means you still have options.

Treatment Options: From Removal to Transplant

For early-stage HCC, there are three main ways to cure it:

- Resection: Surgically removing the tumor. This works if your liver is still healthy enough to handle surgery and the tumor is in one spot.

- Radiofrequency ablation (RFA): A needle is inserted into the tumor, and heat burns it away. It’s minimally invasive, often done as an outpatient, and works best for tumors under 3 cm.

- Liver transplant: The gold standard-if you’re eligible. You get a new liver, and the cancer is gone. But you need to meet strict criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors all under 3 cm, with no spread outside the liver.

For more advanced cases, options include targeted drugs like sorafenib, immunotherapy, or chemoembolization. But these aren’t cures. They’re ways to slow the disease. That’s why catching it early is everything.

Who Gets Screened? Not Everyone

Here’s where things get complicated. Not every person with cirrhosis gets the same advice.

The AASLD says: screen everyone with Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) Class A or B cirrhosis. That’s most people. But if you’re in Class C-your liver is failing-you’re not a good candidate for aggressive treatment. Your life expectancy is under two years. So screening isn’t recommended… unless you’re on a transplant list.

Meanwhile, the EASL took a bold new step in 2023: they’re not screening everyone. They’re screening based on risk. If your annual chance of getting HCC is below 1.5%, they say you might not need regular scans. How do they calculate that? Using tools like the aMAP score, which looks at your age, gender, albumin, bilirubin, and platelet count. If your score puts you in the low-risk group, you might only need a scan once a year-or not at all.

This is a major shift. It’s not about ignoring risk. It’s about focusing resources where they matter most. In Australia, where liver disease is rising due to hepatitis C and fatty liver, this could save millions in healthcare costs without missing a single life.

The Real Problem: Nobody’s Doing It

Here’s the ugly truth: even though guidelines are clear, most people with cirrhosis aren’t getting screened.

In the U.S., only 41% of cirrhotic patients with HCC had been screened before diagnosis. In Australia, the numbers are similar. Why? Three big reasons:

- Doctors don’t remind patients. If your GP doesn’t have an automated alert in their system when you’re diagnosed with cirrhosis, they might forget. Only 45% of clinics have formal screening pathways.

- Patients miss appointments. About one in three people with cirrhosis don’t show up for their next scan. Reasons? Transportation, cost, confusion, or just feeling fine.

- There’s no clear system. Who orders the scan? Who schedules it? Who follows up? In many places, nobody. It falls through the cracks.

One study found that when clinics used patient navigators-trained staff who call, remind, and help book appointments-no-show rates dropped from 32% to 14%. When EHR systems automatically triggered referrals after a cirrhosis diagnosis, the time to first scan dropped from 142 days to 67.

What’s Coming Next: AI, Biomarkers, and Faster Scans

The future of HCC surveillance isn’t just more ultrasounds. It’s smarter tools.

AI-assisted ultrasound systems, like Medtronic’s LiverAssist, are already FDA-approved. They help technicians spot tiny tumors that humans might miss-improving detection by 18-22%. That’s not a gimmick. That’s life-saving.

And then there are blood tests. The GALAD score-combining gender, age, AFP, AFP-L3, and DCP-is showing 85% sensitivity for early HCC. If validated, it could become a routine blood test alongside liver function panels. No more waiting for a scan.

Abbreviated MRI protocols are also on the horizon. Instead of 30 minutes, you’ll get a full liver scan in 5-7 minutes. Cost? Around $350. For high-risk patients, this might replace ultrasound entirely by 2027.

By late 2024, the AASLD is expected to update its guidelines. Preliminary drafts suggest stronger support for risk-based screening and the use of biomarkers. The future isn’t just about screening more-it’s about screening smarter.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you have cirrhosis:

- Ask your doctor: "Am I on a surveillance plan?"

- Confirm: "Is my next ultrasound scheduled for six months from now?"

- Ask: "Should I get an AFP test?" (Answer: Only if your doctor thinks it adds value.)

- If you’re not sure you have cirrhosis: get tested. A simple FibroScan or blood test can tell you.

If you’re a caregiver or family member: remind them. Set calendar alerts. Drive them to appointments. Make it non-negotiable.

Because here’s the bottom line: HCC is preventable-not by avoiding alcohol or curing hepatitis alone-but by consistent, lifelong surveillance. You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to show up. Every six months.

Can you survive hepatocellular carcinoma if caught early?

Yes. If HCC is found at Stage 0 or A-usually through surveillance-treatment success rates are high. Resection, radiofrequency ablation, or liver transplant can cure the cancer in up to 70% of cases. Survival beyond five years is common when tumors are under 2 cm and haven’t spread.

Is ultrasound enough to detect liver cancer?

Ultrasound is the recommended first step, but it’s not perfect. It can miss tumors smaller than 1 cm or hide them in scarred liver tissue. That’s why any suspicious finding must be followed up with a contrast CT or MRI. These are far more accurate, with 80-90% sensitivity for confirming HCC.

Do I need to get screened if I have fatty liver disease?

Only if you’ve progressed to cirrhosis. Most people with fatty liver don’t develop scarring. But if you have advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis-even from NAFLD-you’re at risk. Screening is recommended. Annual risk for HCC in cirrhotic NAFLD is 1-3%, which meets the threshold for surveillance.

Why is AFP testing not always recommended?

AFP isn’t reliable. It can be elevated due to hepatitis flare-ups, pregnancy, or even benign liver growths. It can also be normal in people with HCC. Because of this, major guidelines treat it as a supplemental tool-not a standalone test. A high AFP triggers imaging, but a normal AFP doesn’t rule out cancer.

Can I skip screening if I feel fine?

Absolutely not. HCC doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s advanced. Feeling fine doesn’t mean you’re cancer-free. In fact, most patients diagnosed with early HCC report no symptoms at all. Surveillance is about catching cancer before you feel it. Skipping it is the biggest risk you can take.

Ashley Paashuis

21 Feb, 2026

Thank you for laying this out so clearly. I’ve been managing cirrhosis for five years now, and this is the first time I’ve seen a breakdown that actually makes sense. The six-month ultrasound rule isn’t just a suggestion-it’s a lifeline. I show up every time, even when I feel fine. Because feeling fine doesn’t mean I’m safe.

Oana Iordachescu

23 Feb, 2026

Let’s not ignore the elephant in the room: pharmaceutical companies profit from surveillance. Ultrasounds, MRIs, AFP tests-they’re all revenue streams. The real question is: are we being protected… or monetized?

Michaela Jorstad

24 Feb, 2026

I’m so glad someone finally said this: surveillance isn’t about fear. It’s about agency. I used to skip my scans because I didn’t want to ‘think about it.’ Now? I schedule them like dentist appointments. No excuses. My liver deserves that much.

Chris Beeley

24 Feb, 2026

Look, I’ve read every guideline, every meta-analysis, every randomized controlled trial from the last decade-and I’m here to tell you, the entire surveillance paradigm is built on shaky foundations. The 50-70% survival rate? It’s cherry-picked from select cohorts. The real-world numbers? More like 30%, especially in underserved populations. And don’t get me started on LI-RADS-radiologists still argue over Category 4s like it’s a theological debate. We’re not saving lives; we’re performing performative medicine.

Arshdeep Singh

24 Feb, 2026

Bro, you think screening saves lives? Nah. It just makes people feel like they’re doing something. Meanwhile, your liver’s still fucked. Stop chasing scans and start fixing your damn diet. No alcohol. No sugar. No processed food. That’s the real cure. Not some machine that beeps.

James Roberts

26 Feb, 2026

Wow. So we’re telling people with cirrhosis to get screened every six months… but only 41% of them do? And we’re surprised they die? Let me guess-no one told them it was free. Or maybe they had to take two buses and a train to get there. This isn’t a medical problem. It’s a social justice crisis. Someone needs to send a van. With snacks. And a person who says, ‘I’ll go with you.’

Danielle Gerrish

27 Feb, 2026

I cried reading this. My mom had cirrhosis from hepatitis C. She refused screening because she said, ‘If it’s going to kill me, I don’t want to know.’ She passed last year. She was 62. I wish someone had told her-gently, lovingly-that this wasn’t about doom. It was about time. Time to travel. Time with grandkids. Time to say goodbye on her own terms. Please, if you’re reading this and you have cirrhosis-don’t wait. Not for ‘feeling ready.’ Not for ‘being strong.’ Just go. For you.

Freddy King

28 Feb, 2026

AI-assisted ultrasound? Cool. But let’s be real-the real bottleneck isn’t detection. It’s interpretation. Radiologists are overworked, underpaid, and drowning in noise. Even with AI, you still need a human to say, ‘This isn’t a tumor-it’s a benign hemangioma.’ And guess who’s not trained for that? The entire system is a house of cards built on goodwill and caffeine.

Greg Scott

1 Mar, 2026

My doctor just said ‘get an ultrasound’ and moved on. No follow-up. No reminder. No explanation. I didn’t even know I was supposed to come back. I’m lucky I remembered. This needs to be automated. Like, seriously. If you have cirrhosis, your EHR should scream at your doctor until they schedule it.

Scott Dunne

3 Mar, 2026

Irish healthcare doesn’t even offer this consistently. And yet, here in the U.S., you’re expected to jump through hoops while the NHS just… doesn’t. This is why we need centralized systems-not American-style patchwork. Screening should be universal. Not conditional. Not risk-based. Just done.

Jeremy Williams

3 Mar, 2026

In my village in rural India, cirrhosis is common-but so is fatalism. People say, ‘It’s God’s will.’ I’ve started organizing monthly transport to the clinic. We pool money for gas. One woman, 71, got her first ultrasound in 12 years. The tumor was 1.8 cm. She’s getting RFA next week. It’s not glamorous. But it’s life.

Tommy Chapman

3 Mar, 2026

Why are we still using ultrasound? It’s 2024. We’ve got MRIs that can scan your liver in 5 minutes. Why are we clinging to 1990s tech because it’s cheap? This isn’t progress. It’s negligence. If you’re rich, you get the real scan. If you’re poor? You get blurry shadows and hope. That’s not healthcare. That’s class warfare.

Irish Council

4 Mar, 2026

Ultrasound every 6 months? Nah. I got a FibroScan last year. Zero issues. Done.

Laura B

5 Mar, 2026

My sister was diagnosed with cirrhosis after her third ER visit. She’s now on the transplant list. We’re doing everything right-screening, diet, no alcohol. But here’s what no one tells you: the emotional toll is heavier than the physical one. You start seeing every ache as a tumor. Every fatigue as a sign. It’s exhausting. I wish there was more support for the mental side of surveillance-not just the medical.