What Exactly Is an Ear Infection in Kids?

When a child has an ear infection, it’s usually acute otitis media - a sudden infection in the middle ear, the space behind the eardrum. It’s not just a stuffy ear. It’s pain, fever, fussiness, and sometimes fluid draining out. About 83% of kids get at least one by age 3. Most happen between 6 and 24 months, when their Eustachian tubes are short and horizontal, making it easier for germs to travel from the nose and throat to the ear.

The diagnosis isn’t just based on crying or tugging at the ear. Doctors need to see three things: signs of recent illness (like fever or irritability), fluid behind the eardrum (seen with an otoscope as a bulging, dull, or red eardrum), and clear signs of inflammation - not just redness, but actual swelling or pus. If the eardrum looks normal, it’s probably not an infection.

Why Antibiotics Aren’t Always the Answer

For years, doctors handed out antibiotics like candy for ear infections. But here’s the truth: 60% to 80% of these infections clear up on their own, no pills needed. The American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidelines in 2013 to reflect this. Now, watchful waiting is the standard for many kids - not because doctors are lazy, but because the evidence is clear.

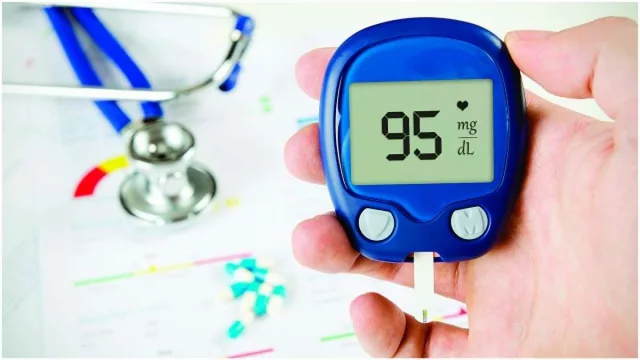

Antibiotics help most in severe cases. If your child is under 6 months old, has a fever over 102.2°F, has ear pain lasting more than 48 hours, or has fluid draining from the ear, antibiotics are necessary. For kids over 2 with mild symptoms and just one infected ear? You can wait. Most will feel better in 24 to 48 hours without any medicine.

When antibiotics are needed, high-dose amoxicillin is the first choice - 80 to 90 mg per kg of body weight per day. For kids allergic to penicillin, alternatives like cefdinir or clindamycin are used. The course length depends on age: 10 days for babies under 2, 7 days for ages 2 to 5, and just 5 days for older kids with mild cases. Giving antibiotics longer than needed doesn’t help - it just increases the risk of side effects and antibiotic resistance.

Watchful Waiting: What It Really Means

Watchful waiting isn’t ignoring the problem. It’s a plan. You’re giving the body time to heal while staying alert for warning signs. The CDC and AAP recommend it for:

- Children 6 to 23 months with infection in just one ear and no severe symptoms

- Children 24 months and older with infection in one or both ears, as long as symptoms are mild

Parents get a safety-net prescription - a back-up antibiotic to fill only if the child gets worse after 48 hours. Studies show that about two out of three families never use it. Symptoms improve in most kids within two days. Fever drops, crying stops, sleep returns.

But watchful waiting doesn’t mean no pain relief. Pain is the biggest issue. Acetaminophen or ibuprofen should be given regularly - every 4 to 6 hours - even if you’re waiting to see if antibiotics are needed. A 2017 study found that nearly 70% of kids with ear infections had moderate to severe pain, but only 37% got proper pain meds. That’s a gap we can fix right now.

When Tubes Are the Right Choice - and When They’re Not

Tympanostomy tubes are tiny plastic or metal cylinders placed through the eardrum to let air in and fluid out. They’re common - about 667,000 are inserted in U.S. kids every year. But they’re not a cure-all.

Tubes are recommended only when a child has:

- Three or more ear infections in six months, or four or more in a year, with at least one in the last six months

- Fluid stuck behind the eardrum for three months or longer, with documented hearing loss of 40 dB or more

That last part is critical. If a child has frequent infections but no hearing loss, tubes often don’t help. A 2016 review warned that tubes are overused in kids who just have “recurrent” infections without any real impact on hearing or speech development.

Tubes usually stay in place 6 to 18 months and fall out on their own. They reduce infections by about half in the first six months, but after that, the benefit fades. Some kids still get infections with tubes. Others get scarring on the eardrum or even a small hole that doesn’t heal.

They’re not for every child with a few ear infections. They’re for kids whose hearing or development is actually at risk.

What’s Changing in Treatment Guidelines

Guidelines keep evolving. In 2013, the AAP lowered the age for automatic antibiotics from under 24 months to under 6 months - because studies showed no real benefit in older babies with mild cases. Since then, vaccination has helped too. The PCV13 pneumococcal vaccine, introduced in 2010, cut ear infection rates by 12% and recurrent infections by 20% in large studies.

Antibiotic prescribing has dropped from 95% in 1995 to 61% in 2022. That’s progress. But it’s uneven. In some clinics, 78% of kids still get antibiotics right away. In others, it’s 52%. Why? Parent pressure. Time limits. Uncertainty in diagnosis.

New guidelines expected in 2024 will likely tighten tube criteria even more - requiring proof of hearing loss before surgery for all kids. They’ll also expand watchful waiting to include some kids with bilateral infections, if symptoms are mild.

What Parents Can Do Right Now

Here’s what works:

- Use pain relief first - acetaminophen or ibuprofen - every few hours, even if you’re waiting to see if antibiotics are needed.

- Don’t use decongestants or antihistamines. They don’t help ear infections and can cause drowsiness or upset stomach.

- Ask for a safety-net prescription if you’re doing watchful waiting. Keep it on hand, but only fill it if symptoms get worse after 48 hours.

- Follow up with your doctor if the child isn’t better in 48 to 72 hours, or if they develop a high fever, drainage, or seem unusually lethargic.

- Ask: “Is this infection severe? Is my child’s hearing affected? Are tubes really necessary?” Don’t accept “just to be safe” as a reason.

Most kids outgrow ear infections by age 5. Their tubes grow longer, their immune systems get stronger. The goal isn’t to prevent every single infection - it’s to protect their hearing, their sleep, and their quality of life.

Why Overusing Antibiotics Matters

Every time we give an antibiotic unnecessarily, we help bacteria learn how to survive. In the U.S., inappropriate antibiotic use for ear infections contributes to 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections every year. That means infections that once responded to simple pills now need stronger drugs, hospital stays, or even surgery.

Dr. Richard Rosenfeld, who helped write the 2013 AAP guidelines, says watchful waiting has cut antibiotic prescriptions for ear infections by 35% since 2000 - without increasing complications. That’s not just smart medicine. It’s saving lives.

Final Thought: Trust the Process

It’s hard to watch your child in pain and not reach for a pill. But sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is wait - with pain relief in hand, a plan in place, and a doctor you trust. Most ear infections aren’t emergencies. They’re temporary. And letting the body heal itself, when it can, protects not just your child - but the next generation too.

Scarlett Walker

15 Nov, 2025

Just wanted to say THANK YOU for this post. My 18-month-old had his third ear infection last month and we went the watchful waiting route - gave him ibuprofen every 6 hours, kept him cozy, and by day 3 he was back to his silly self. No antibiotics needed. It felt scary at first, but honestly? Best decision we’ve made.

Sean Evans

16 Nov, 2025

LOL at the ‘watchful waiting’ nonsense. My kid was screaming for 72 hours and you want me to just ‘wait’? 😒 Antibiotics are not ‘overused’ - they’re underutilized by cowards who think nature will fix everything. My daughter had a ruptured eardrum because her mom waited too long. Don’t be that parent.

Brittany C

18 Nov, 2025

Sean - I get your frustration, but the data doesn’t lie. The AAP’s 2013 guidelines were based on RCTs with thousands of kids. Most ear infections are viral, and antibiotics don’t touch viruses. Pain management? That’s the real priority. I’m an ENT nurse, and I’ve seen kids with tubes still get infections - and kids with zero meds heal perfectly. It’s not about being lazy, it’s about being evidence-based. Also, emoji for pain: 🤕➡️😌

Ashley Durance

19 Nov, 2025

Brittany, you’re cherry-picking. You say ‘my kid healed’ - but what about the 20% who develop hearing loss or chronic effusion? You’re normalizing neglect. If a child has recurrent infections, the standard of care is not ‘wait and pray.’ It’s diagnostic imaging and otoscopic follow-up. You’re lucky. Others aren’t.

Scott Saleska

20 Nov, 2025

Ashley, I hear you - but I’ve worked in pediatric clinics for 12 years. We had a kid last year with bilateral fluid for 5 months, no hearing loss, no speech delay - parents were pressured into tubes. Turned out it was just allergies. Tubes weren’t needed. The real problem? Doctors who don’t take the time to explain the difference between ‘recurrent’ and ‘chronic.’ It’s not neglect - it’s miscommunication.

Brian Bell

20 Nov, 2025

Y’all are overthinking this. My son got 4 ear infections in 6 months. We did the 48-hour wait, used Tylenol, and he was fine. Tubes? Nope. He’s 4 now and hasn’t had one since. Kids heal. Let them. 🤝

Anjan Patel

21 Nov, 2025

Ohhhhhhhhh! So now we are supposed to trust the ‘guidelines’? Who wrote these guidelines? White doctors in ivory towers who’ve never seen a crying baby in a village with no pharmacy? In India, we don’t have ‘safety-net prescriptions’ - we have grandmas with warm oil and prayers. You think a 12-month-old in Bihar has access to ibuprofen? This is privilege medicine disguised as science. 🌏💔

Hrudananda Rath

22 Nov, 2025

While I appreciate the clinical rigor of the foregoing exposition, I must interject with the gravest of concerns: the normalization of passive management in pediatric otitis media constitutes a subtle yet insidious erosion of medical authority. The invocation of ‘watchful waiting’ as a default, absent objective biomarkers of severity, betrays a troubling capitulation to parental anxiety - and, by extension, a devaluation of the physician’s diagnostic prerogative. The data, however robust, cannot supplant clinical judgment - especially when applied uniformly across heterogeneous populations. One must ask: Is the reduction in antibiotic prescriptions a triumph of evidence, or a failure of vigilance?

Nathan Hsu

24 Nov, 2025

As someone who’s lived through three kids, two tubes, and one ruptured eardrum - I’m here to say: the system works - but only if you’re informed. Pain relief first. Safety-net script second. Doctor follow-up third. And never, ever, use cold medicine. It’s not magic. It’s not science. It’s just sugar water with side effects. Also - PCV13? Life-changing. My youngest? Zero infections after the vaccine. Just saying.