When your liver fails, there’s no backup. No reset button. No pill that can replace what’s broken. For thousands of people each year, a liver transplant is the only chance to live. It’s not a simple fix-it’s a life-altering journey that begins long before the operating room and lasts a lifetime. This isn’t just about surgery. It’s about who gets chosen, how the procedure works, and what happens after the new liver is in place.

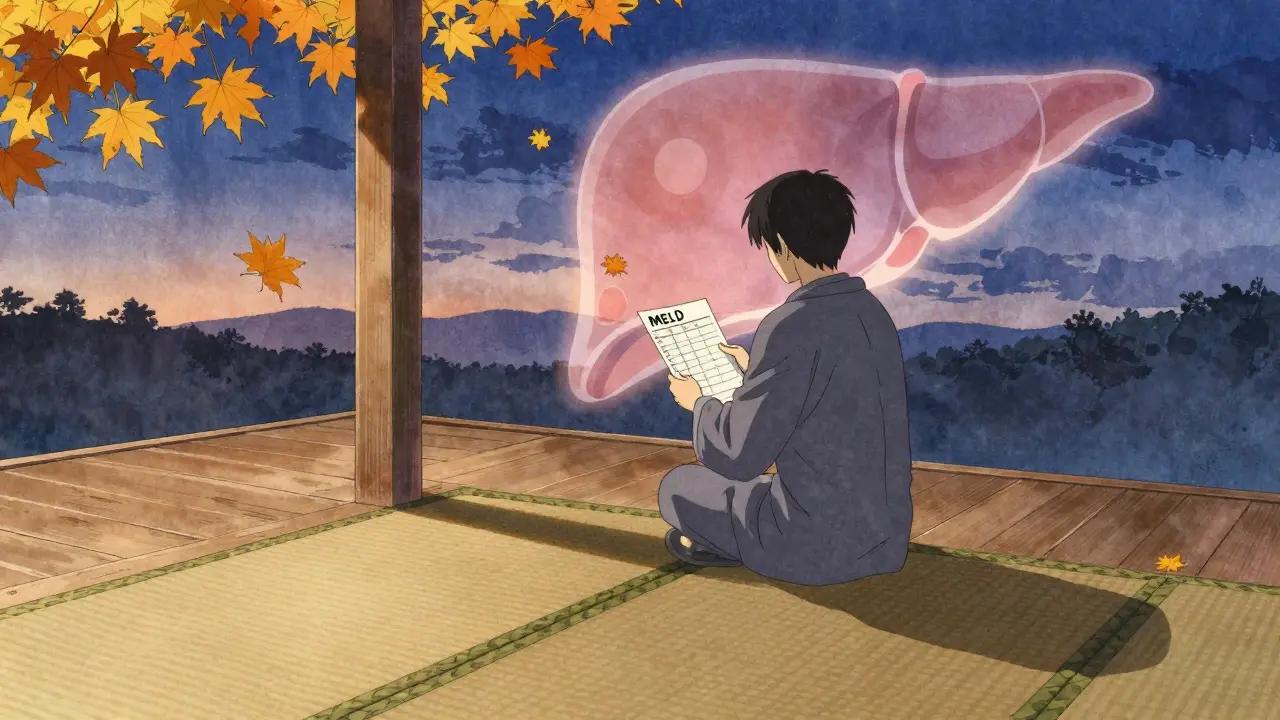

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system is strict because organs are scarce. In the U.S., about 8,000 liver transplants happen each year, but over 10,000 people are on the waiting list. So how do they decide who gets priority? The answer is the MELD score-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the sicker you are. A score of 6 means you’re relatively stable. A score of 40 means you’re in critical condition. Patients with MELD scores above 25 are at the top of the list. But it’s not just about numbers. Certain conditions automatically disqualify someone. Active drug or alcohol use? No. Metastatic cancer? No. Severe heart or lung disease that makes surgery too risky? Also no. Even if your liver is failing, your body has to be strong enough to survive the operation and recovery. There’s also the psychosocial evaluation. You need stable housing, someone to help you after surgery, and the ability to take medications exactly as prescribed. One patient on Reddit shared how a single missed appointment delayed his transplant by six months because his insurance didn’t cover transportation. That’s not rare. About 32% of candidates report being denied coverage for pre-transplant tests, according to a 2023 National Transplant Survey. For liver cancer patients, the rules are even tighter. The Milan criteria say you can only qualify if you have one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors each under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level is over 1,000 and doesn’t drop below 500 after treatment, you’re usually excluded unless your case gets special review.Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor

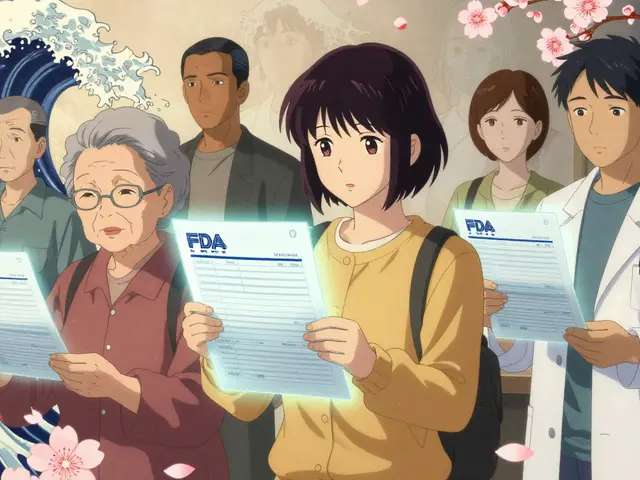

You can get a liver from someone who’s passed away-or from a living donor. About 15% of transplants in the U.S. come from living donors. That’s a growing trend, especially for patients who won’t survive the wait. Living donors are usually healthy adults between 18 and 55. They must have a BMI under 30, no history of liver or heart disease, and must not smoke or drink. Surgeons remove about 55-70% of the donor’s right lobe. The liver regrows in both donor and recipient. Donors typically need 6-8 weeks to recover fully. The risk of death for the donor is low-about 0.2%-but complications like bile leaks or infections happen in 20-30% of cases. The big advantage? Time. For high-MELD patients, waiting for a deceased donor can take a year or more. With a living donor, the transplant can happen in as little as three months. Some centers are pushing boundaries. Columbia University now considers donors with BMI up to 35 if they have excellent liver quality and no other risks. Their 5-year graft survival rate? 92%, compared to the national average of 89%. Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD livers used to have higher complication rates-especially with bile ducts-but new technology is changing that. Machine perfusion, which keeps the liver alive and beating outside the body, has cut biliary complications from 25% to 18% in some centers. The FDA approved the first portable perfusion device in June 2023, extending preservation time from 12 to 24 hours.What Happens During Surgery?

Liver transplant surgery is complex and long-usually 6 to 12 hours. It’s done in three phases. First, the hepatectomy: the surgeon removes your diseased liver. Then comes the anhepatic phase: you have no liver at all. Blood flow is rerouted, and your body survives on temporary support. This part is the most dangerous. The liver normally filters toxins, makes proteins, and regulates blood sugar. Without it, you’re vulnerable to infection, bleeding, and metabolic collapse. Finally, the implantation: the donor liver is placed in. Surgeons connect the major blood vessels and bile ducts. About 85% of transplants use the “piggyback” technique, which leaves the recipient’s inferior vena cava intact. This reduces blood loss and speeds recovery. After surgery, you’re moved to the ICU. Most patients stay there 5-7 days. Total hospital time averages 14-21 days if there are no complications. But recovery doesn’t end there. You’ll need weekly blood tests for the first three months, then biweekly, then monthly. Medication adjustments are constant.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Trade-Off

Your body will try to reject the new liver. It doesn’t know it’s supposed to accept it. That’s why you need immunosuppressants-for the rest of your life. The standard starting regimen is triple therapy: tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors aim for blood levels between 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lower it to 4-8 ng/mL. Too low? Rejection risk goes up. Too high? Kidney damage, tremors, or diabetes kick in. Mycophenolate stops immune cells from multiplying. It’s tough on the stomach-about 30% of patients get nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. It can also lower white blood cell counts, making you more prone to infection. Prednisone, a steroid, was once used long-term. Now, 45% of U.S. transplant centers use steroid-sparing protocols. They drop prednisone after one month. Why? Because it causes weight gain, bone loss, and diabetes. Without it, the risk of new-onset diabetes drops from 28% to 17%. About 15% of patients have acute rejection in the first year. It’s usually caught early through blood tests. Treatment means increasing tacrolimus or adding sirolimus. Long-term, 35% of patients develop kidney problems from tacrolimus. 25% get diabetes. 20% experience nerve issues like shaking or trouble sleeping. There’s hope on the horizon. Researchers at the University of Chicago have successfully weaned 25% of pediatric transplant recipients off all immunosuppressants by age 5 using regulatory T-cell therapy. It’s experimental, but it’s a sign that someday, lifelong drugs might not be necessary.Life After Transplant

The first year is the hardest. You’ll need to avoid crowds, wash your hands constantly, and never skip a dose. One missed pill can trigger rejection. Studies show you need at least 95% adherence to survive. Medication costs are high-$25,000 to $30,000 per year, even with insurance. That doesn’t include doctor visits, lab tests, or hospital stays for complications. Many patients struggle with insurance denials or gaps in coverage. But the payoff is real. Eighty-five percent of patients are alive one year after transplant. Seventy percent make it five years. Many return to work, travel, and even have children. One patient in California, approved after a social worker helped her secure housing and transportation, gave a 4.8/5 review: “They didn’t just save my liver. They saved my life.” Geographic inequality is still a problem. In OPTN Region 9 (California), patients with MELD scores of 25-30 wait an average of 18 months. In Region 2 (Midwest), it’s just 8 months. New policies are trying to fix this. In November 2025, British Columbia changed its rules for Indigenous patients, replacing rigid abstinence requirements with culturally tailored support systems.What’s Changing Now?

The field is evolving fast. The MELD-Na score now includes sodium levels for patients with fluid buildup-helping about 12% more people get priority. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is now the second leading cause of liver transplants, accounting for 18% of cases. In 2010, it was just 3%. Some experts argue the 6-month sobriety rule for alcohol-related liver disease is outdated. Yale researchers found no difference in 5-year survival between patients who stopped drinking for 3 months versus 6 months. Yet most centers still require the longer wait. The liver transplant market is growing. Valued at $2.8 billion in 2023, it’s expected to grow over 5% annually through 2030. But the real progress isn’t in dollars-it’s in survival, in dignity, in second chances.What If You’re Not Eligible?

If you’re turned down, it doesn’t mean the door is closed forever. Some centers allow re-evaluation after addressing issues-like quitting smoking, losing weight, or completing counseling. Others offer bridge therapies: artificial liver devices that keep you alive while you wait for a transplant. But none have proven they can replace a transplant long-term. The truth is, liver transplantation isn’t perfect. It’s expensive, complex, and unfair in who gets access. But for those who make it through, it’s the difference between dying and living. Between watching your grandkids grow up-and not.What is the MELD score and how does it affect my transplant chances?

The MELD score is a number based on three blood tests that show how sick your liver is. It ranges from 6 (mild) to 40 (critical). The higher your score, the higher your priority on the transplant list. It’s the main way centers decide who gets a liver next. If you have liver cancer, special rules apply, and MELD alone won’t guarantee you a transplant.

Can I donate part of my liver to a family member?

Yes, if you’re healthy, between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and don’t use alcohol or drugs. You’ll go through extensive testing to make sure your liver is healthy and your anatomy allows safe removal. Most donors recover fully in 6-8 weeks. The risk of death is very low-about 0.2%-but complications like bile leaks or infection can happen in 20-30% of cases.

How long do I have to be alcohol-free before I can get a transplant?

Most U.S. centers require six months of sobriety before listing. But this rule is being challenged. Yale research shows patients with three months of sobriety have nearly the same 5-year survival as those with six months. Some centers are now allowing shorter periods if patients show strong support and commitment to change.

What are the main side effects of immunosuppressant drugs?

Tacrolimus can cause kidney damage in 35% of patients by year five, diabetes in 25%, and tremors or nerve issues in 20%. Mycophenolate often causes stomach problems in 30% and lowers blood cell counts in 10%. Prednisone, if used long-term, leads to weight gain, bone loss, and high blood sugar. Many centers now stop prednisone after one month to reduce these risks.

How much does a liver transplant cost after surgery?

The first year of care, including medications, lab tests, and doctor visits, costs about $25,000-$30,000 out-of-pocket after insurance. This doesn’t include complications like rejection or infection, which can add tens of thousands more. Many patients struggle with insurance coverage, especially for pre-transplant evaluations and ongoing care.

Can I live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to work, travel, and enjoy normal activities. About 70% survive five years or more. But you’ll need to take immunosuppressants every day, avoid infections, and get regular blood tests. You can’t drink alcohol, and you’ll need to be careful with certain foods and medications. It’s not a cure, but it’s a second chance at life.

Ben Harris

25 Dec, 2025

So let me get this right you're telling me if I miss one damn appointment because my bus broke down I get kicked off the list for six months but some rich guy with a private driver gets priority because he can afford to show up on time? This system is rigged and everyone knows it

Justin James

26 Dec, 2025

Have you ever stopped to think that the whole transplant system is just a front for Big Pharma to keep selling immunosuppressants forever? They don't want you cured they want you dependent because every pill you take generates billions in revenue and if they ever find a way to wean people off drugs like that T-cell therapy at Chicago then the entire industry collapses overnight and no one talks about this because the FDA and the transplant centers are all in bed together with the drug companies and the insurance moguls who profit from lifelong dependency and you think your 95% adherence is saving your life but really it's just keeping the stock prices up

Zabihullah Saleh

27 Dec, 2025

It's strange isn't it how we treat organs like commodities when they're really just the result of a lifetime of breaths and meals and quiet moments with loved ones. We assign scores and waitlists like they're tickets to a concert but the truth is every liver carries the echo of someone's laughter their fears their regrets. Maybe the real question isn't who gets the organ but who gets to remember them after they're gone

Rick Kimberly

28 Dec, 2025

While the MELD-Na score represents a significant advancement in objective patient prioritization it is imperative to acknowledge the persistent disparities in geographic allocation. The variance between OPTN Region 9 and Region 2 underscores systemic inefficiencies that warrant immediate policy reform to ensure equitable access irrespective of socioeconomic or demographic factors

Terry Free

29 Dec, 2025

Oh so now you need to be sober for six months but you can still be a diabetic with three stents and a pacemaker? Cool cool so the real criteria is you gotta be broke enough to quit drinking but rich enough to afford the meds that keep you alive. Makes perfect sense

Lindsay Hensel

30 Dec, 2025

My brother waited two years. He lost his job. His wife left. He cried every night in the hospital waiting room. When they finally called his name he said it didn't feel like a miracle. It felt like a debt he could never repay. We don't talk about that part enough.

sagar patel

31 Dec, 2025

Living donor surgery risk is 0.2 percent death rate. But bile leak infection complications occur in 20 to 30 percent. This is not acceptable. Medical ethics require informed consent. Donors are not statistics.

Linda B.

1 Jan, 2026

Machine perfusion devices FDA approved June 2023 right. And yet somehow the same people who approved that are the ones who still make you wait six months to prove you're not a drunk. Coincidence? I think not

Christopher King

2 Jan, 2026

They say the liver regrows but what if it remembers? What if the donor liver still carries the trauma of the person it came from? The grief the anger the secrets? What if your new liver starts dreaming in someone else's memories? I read a case where a recipient started craving pickles and listening to 80s rock and the donor was a guy who owned a diner and played Springsteen every Sunday. Coincidence? Or is your liver whispering to you now?

Bailey Adkison

2 Jan, 2026

They say 70 percent survive five years. But what about the ones who die because they couldn't afford the $25k a year in meds? The system doesn't fail the liver. It fails the people. And you call that progress?

Gary Hartung

3 Jan, 2026

Let's be honest here - the whole transplant narrative is just a feel-good marketing campaign for hospitals. They show you the happy families and the five-year survival stats but never the guy who spent his life savings on tacrolimus and still lost his kidneys. They don't want you to know that 35 percent of transplant patients end up on dialysis. That's not a success story. That's a financial trap dressed in a lab coat.

Carlos Narvaez

3 Jan, 2026

Living donor transplants are the future. 92 percent graft survival? That's not a number. That's hope with a scalpel.