When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might assume the pharmacist just fills what the doctor ordered. But in many parts of the U.S., that’s not the whole story. Today, pharmacists can do far more than count pills. They can swap medications, adjust doses, even prescribe certain drugs-all within legally defined limits. This is pharmacist substitution authority, and it’s changing how millions of Americans get their care.

What Exactly Is Pharmacist Substitution Authority?

Pharmacist substitution authority means the legal right for pharmacists to make changes to a prescription without going back to the prescriber. It’s not about guessing or improvising. It’s a structured, regulated process that varies by state. The most common form is generic substitution: if a brand-name drug is prescribed but a generic version is available and allowed, the pharmacist can switch it unless the doctor writes “dispensed as written.” This is legal in all 50 states and has been standard for decades. But it goes further. In some states, pharmacists can do something called therapeutic interchange. That means they can swap a drug for another in the same class-even if it’s not the exact same chemical. For example, if a patient is prescribed one statin for cholesterol and the pharmacy runs out, a pharmacist in Arkansas, Idaho, or Kentucky can switch to another statin, as long as the prescriber marked the prescription with “therapeutic substitution allowed.” The pharmacist must then notify the doctor and inform the patient about the change. In Idaho, they’re required to get the patient’s consent before swapping. Then there’s prescription adaptation. This lets pharmacists tweak a patient’s existing medication-change the dose, frequency, or duration-without calling the doctor. It’s especially useful in rural areas where patients might drive hours to see a provider just to adjust a blood pressure pill. States like New Mexico and Colorado allow this under statewide protocols, meaning the board of pharmacy sets the rules, not each doctor.How Do Collaborative Practice Agreements Work?

Another big piece of substitution authority is the Collaborative Practice Agreement (CPA). Every state and D.C. allows these, but how they’re used differs wildly. A CPA is a written agreement between a pharmacist and one or more prescribers. It lays out exactly what the pharmacist can do: when to start a medication, when to stop it, which tests to order, and when to refer the patient back to a doctor. In some states, CPAs are simple and used mostly for minor conditions like allergies or minor infections. In others, like Minnesota or Oregon, pharmacists under CPAs can manage chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension independently. The agreement must include clear decision thresholds: for example, if a patient’s blood sugar stays above 200 mg/dL for three days, the pharmacist can add metformin. They must document everything in the shared health record, and the prescriber stays in the loop. Recent trends show pharmacists are gaining more autonomy in these agreements. Instead of needing a doctor to approve every change, many new CPAs let pharmacists drive the protocol. That means less back-and-forth and faster care-especially important when patients can’t get an appointment for weeks.State-by-State Differences: Who Can Prescribe What?

The rules aren’t the same across the country. Here’s how some states are pushing boundaries:- Maryland: Pharmacists can prescribe birth control to anyone 18 or older. Medicaid must cover it, and pharmacists are officially recognized as providers.

- Maine: Pharmacists can prescribe nicotine replacement therapy (patches, gum) without a doctor’s script.

- California: They don’t say “prescribe.” They say “furnish.” Pharmacists can furnish hormonal contraceptives, emergency contraception, and naloxone (the opioid overdose reversal drug) under standing orders.

- New Mexico and Colorado: The state pharmacy board sets statewide protocols. That means if the board says pharmacists can give flu shots or treat strep throat, they can-no new law needed each time.

Why Is This Changing Now?

The push for expanded authority isn’t random. It’s a response to real problems. Over 60 million Americans live in areas with too few doctors-called Health Professional Shortage Areas. In rural towns, the nearest primary care provider might be 50 miles away. Pharmacies, on the other hand, are everywhere. There are more than 68,000 pharmacies in the U.S., many open evenings and weekends. When someone needs a flu shot, a refill on their blood pressure pill, or naloxone after an overdose, the pharmacy is often the only place they can get help fast. Physician shortages are getting worse. The Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a shortfall of 124,000 doctors by 2034. Pharmacists, however, are graduating in large numbers-over 15,000 each year. Their training includes pharmacology, drug interactions, dosing, and patient counseling. They’re already checking for dangerous combinations when filling prescriptions. Why not let them do more? Legislative activity is exploding. In 2025 alone, 211 bills were introduced in 44 states to expand pharmacist scope. Sixteen of those bills became law. That’s more than double the pace from just five years ago. At the federal level, the Ensuring Community Access to Pharmacist Services Act (ECAPS) is pending. If passed, it would require Medicare Part B to pay for services pharmacists provide-like testing, vaccinations, and chronic disease management. That’s a game-changer. If Medicare pays, private insurers will follow.What Are the Risks and Pushback?

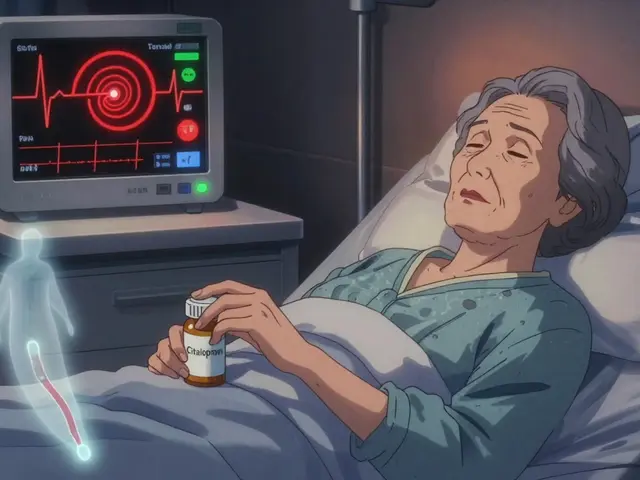

Not everyone supports this shift. The American Medical Association has long warned that pharmacists aren’t trained like physicians. They point to differences in clinical decision-making, diagnostic skills, and handling complex cases. Their policy D-120.920 calls for studying pharmacists who refuse to fill valid prescriptions-a concern that’s often misunderstood. The issue isn’t about pharmacists refusing to fill legal scripts; it’s about moral objections to certain drugs, like emergency contraception. That’s a separate ethical debate. Another concern is corporate influence. Big pharmacy chains like CVS and Walgreens have lobbied hard for expanded authority. Critics worry profit motives could drive decisions, not patient care. But data doesn’t support that fear. Studies from the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association show that pharmacist-led care improves adherence, reduces hospitalizations, and lowers costs-regardless of setting. The real risk isn’t pharmacists overstepping. It’s inconsistent rules. If a pharmacist in Ohio can prescribe birth control but one in Texas can’t, patients moving between states face gaps in care. And without clear reimbursement rules, many pharmacists can’t afford to offer these services-even if the law lets them.

What Does This Mean for Patients?

For you, the patient, this means faster, more convenient care. Need a refill on your asthma inhaler? Your pharmacist can renew it under a standing order. Got a sore throat? You can walk in, get tested, and walk out with antibiotics-all in 20 minutes. No appointment. No waiting. No extra cost if your insurance covers it. You also get better safety. Pharmacists catch drug interactions others miss. In one study, pharmacists identified 82% of potentially dangerous medication combinations that doctors overlooked. They’re trained to spot red flags: a patient on five blood pressure pills, or someone taking opioids with muscle relaxants. That’s not just convenience-it’s life-saving. But you need to know your rights. If your pharmacist wants to swap a drug, ask: “Why?” “Is this safe for me?” “Did my doctor approve this?” You have the right to say no. You also have the right to ask for your original prescription back if you’re uncomfortable.What’s Next for Pharmacist Authority?

The trend is clear: pharmacists are becoming clinical providers, not just dispensers. The next five years will see more states adopt independent prescribing for common conditions-like UTIs, sinus infections, and skin rashes. Some may even allow pharmacists to order lab tests and interpret results. The big hurdle? Reimbursement. Until insurance companies and Medicare pay for these services, many pharmacists won’t offer them. ECAPS could fix that. If it passes, we’ll see a wave of new pharmacist-run clinics in pharmacies, grocery stores, and even schools. What’s also growing is the role of technology. Electronic health records now link pharmacies to hospitals and clinics. Pharmacists can see your full history, not just your last prescription. That’s how they make smart substitutions-because they know what you’ve taken before, what worked, and what didn’t.FAQ

Can my pharmacist change my prescription without telling my doctor?

In most cases, no. For generic substitution, they don’t need to notify the doctor. But for therapeutic interchange or prescription adaptation, state laws require them to inform the prescriber within a set timeframe-usually 24 to 72 hours. This keeps your medical record accurate and ensures your doctor stays involved in your care.

Do I have to accept a drug swap from my pharmacist?

Absolutely not. You have the right to refuse any substitution, even if it’s legal and safe. If your pharmacist suggests a change, ask why. If you’re unsure, ask to speak with your doctor. Your consent is required in states like Idaho and others with strong patient protection laws.

Can pharmacists prescribe antibiotics?

In some states, yes. States like Oregon, Washington, and California allow pharmacists to prescribe antibiotics for specific conditions like urinary tract infections or strep throat under standing orders or collaborative agreements. They must first assess your symptoms, rule out serious causes, and document everything. This isn’t available everywhere, so check your state’s rules.

Why don’t all pharmacies offer these services?

Two main reasons: reimbursement and training. Even if the law allows it, if insurance won’t pay for the service, the pharmacy can’t afford to offer it. Also, not all pharmacists are trained in clinical decision-making. Many still work under old models focused on dispensing. As more states adopt payment models and training programs, this will change.

Are pharmacists as safe as doctors when prescribing?

For the conditions they’re authorized to treat, studies show they’re just as safe. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open found that pharmacist-managed care for hypertension and diabetes led to outcomes equal to or better than physician care. Pharmacists don’t handle complex, multi-system diseases-but for routine, well-defined conditions, their expertise in medications makes them ideal providers.

Robin Williams

15 Jan, 2026

pharmacists are basically the unsung heroes of healthcare. i mean, who else is gonna catch that you’re on 7 meds that all fight each other? doctors are swamped, nurses are burnt out, but the pharmacist? they’re there, checking your script like a hawk. finally someone who actually knows what the hell they’re talking about.

Scottie Baker

17 Jan, 2026

this is long overdue. my grandma had to drive 90 minutes to get her blood pressure med adjusted. last month she walked into the pharmacy, got it changed in 10 minutes, and was home before her soup got cold. if you’re mad about this, you’re mad because you don’t want people helping each other.

Gregory Parschauer

17 Jan, 2026

Let me be perfectly clear: pharmacists are not physicians. They are trained in pharmaceutical chemistry and dispensing logistics-not differential diagnosis, not pathophysiology, not acute clinical decision-making. Expanding their scope under the guise of ‘access’ is a dangerous precedent that undermines the integrity of the entire medical hierarchy. This isn’t efficiency-it’s erosion. And don’t give me that ‘pharmacists catch interactions’ nonsense; that’s their job, not a justification for prescribing antibiotics like they’re handing out candy at a parade.

Anny Kaettano

18 Jan, 2026

I’ve worked in community pharmacy for 18 years, and I can tell you-this isn’t about replacing doctors. It’s about filling gaps where care is *literally* nonexistent. I had a diabetic patient who couldn’t afford to miss work for a doctor’s visit. We adjusted her insulin under protocol, monitored her A1c, and now she’s stable. No hospitalizations. No ER visits. Just a pharmacist who cared enough to act. This isn’t radical-it’s rational.

laura Drever

19 Jan, 2026

pharmacist prescribe? lol. sure. next theyll be doing cts and appendectomies. why not just let the guy at the drive thru write scripts too. lazy system. lazy laws. lazy people. just sayin

John Tran

21 Jan, 2026

You know what this really is? It’s capitalism sneaking into the sacred space of healing. We’ve turned medicine into a product, and pharmacists into corporate agents with white coats. The real issue isn’t access-it’s the commodification of human health. When your blood pressure med becomes a ‘convenience service’ like a coffee refill, we’ve lost something fundamental. The soul of medicine isn’t in the pharmacy counter-it’s in the relationship between healer and patient. And that can’t be standardized, franchised, or optimized.

mike swinchoski

21 Jan, 2026

I don't care if you're a pharmacist or a rocket scientist. If you didn't go to med school, you don't get to decide what medicine I take. That's not 'access,' that's arrogance. You think you know better than a doctor? You don't. You count pills. That's it. Stop pretending you're a doctor.

Trevor Whipple

23 Jan, 2026

yep. got my flu shot and my azithromycin for sinus infection from my pharmacist last week. doc was booked for 3 weeks. he did a rapid test, checked my vitals, asked me about symptoms, and said ‘go ahead.’ no big deal. no drama. just good care. why is this even a controversy? you guys act like pharmacists are wizards with a license to kill. they’re just doing their damn job better than most docs these days.

Avneet Singh

25 Jan, 2026

This is a textbook case of regulatory capture. Big pharma and corporate pharmacy chains lobbied hard for these laws because it increases volume, reduces overhead, and shifts liability. The ‘patient care’ narrative is just PR. Real clinical outcomes? Minimal data. Real patient safety? Questionable. And let’s not pretend this is about rural access-it’s about profit margins in urban pharmacies with 2000 prescriptions a day.

Pankaj Singh

26 Jan, 2026

You’re all naive. Pharmacists don’t have the training to handle drug interactions in complex polypharmacy cases. You think a 30-minute consultation with a pharmacist is equivalent to a 15-year residency? Wake up. This is dangerous. And the fact that people cheer this on shows how broken the system is. We’re not fixing healthcare-we’re just moving the risk around.

Kimberly Mitchell

27 Jan, 2026

The fact that we even have to debate this says everything. We have over 68,000 pharmacies and a physician shortage that’s worsening by the year. Pharmacists are already doing medication reconciliation, identifying adverse events, and counseling patients daily. This isn’t a power grab-it’s a necessary evolution. The real failure is in the system that forces patients to wait weeks for a refill adjustment. We’re not replacing doctors-we’re supporting them.

Vinaypriy Wane

28 Jan, 2026

I’ve seen both sides. My brother is a doctor. I’m a pharmacist. We’ve argued about this for years. But when my mom couldn’t get to her cardiologist for 6 weeks and her BP spiked to 190/110? I adjusted her lisinopril under protocol, called the doctor, documented everything, and she’s fine now. No one died. No one got hurt. The system worked. And if you’re still mad, maybe you’re scared of change-not because it’s dangerous, but because it’s better than what you’re used to.

Diana Campos Ortiz

30 Jan, 2026

i just want to say thank you to the pharmacists who do this work. i had a bad reaction to a med once and my pharmacist was the only one who noticed. she called my doctor, stayed late, and made sure i was safe. that’s not just a job. that’s care. and i’m so glad we’re finally letting them do more of it.