When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 15% of the original price. That’s a big drop-but it’s only the beginning. The real savings come when a second and then a third generic manufacturer enters the race. These later entrants don’t just add choice-they trigger a chain reaction that slashes prices even further, often cutting costs in half again within months.

Why the second generic changes everything

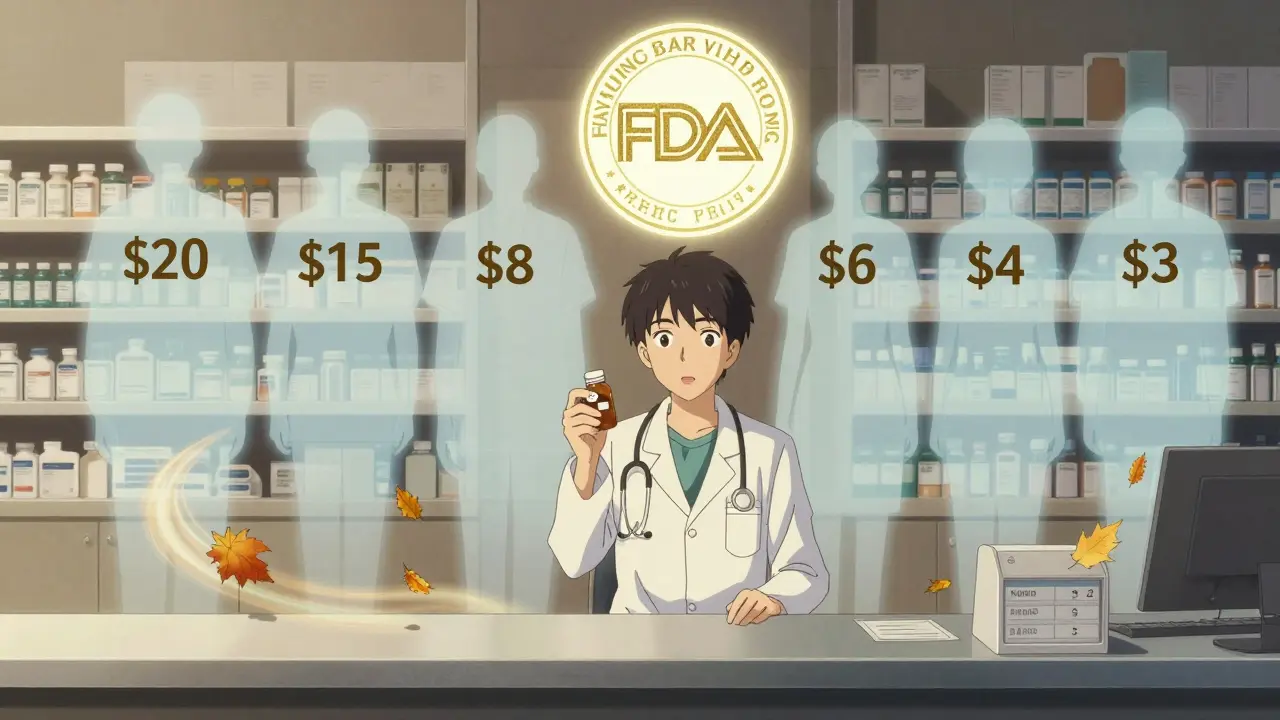

The first generic drug maker doesn’t have much pressure to lower prices. They’re the only option besides the brand, and many pharmacies still pay close to the old brand price because there’s no real competition. But as soon as a second company gets FDA approval and starts selling the same drug, everything shifts. Suddenly, pharmacies and wholesalers have leverage. They can play one supplier off the other. The first generic maker, who thought they had a monopoly, now has to compete-or lose business. Data from the FDA shows that when a second generic enters the market, prices drop to about 58% of the original brand price. That’s not a small adjustment-it’s a 30% plunge from the first generic’s price alone. In real terms, if a brand drug cost $100 per month, the first generic might drop it to $13. The second generic pushes it down to $5.80. For patients paying out of pocket, that’s the difference between affording a medication and skipping doses.The third generic hits the sweet spot

Add a third manufacturer, and prices don’t just keep falling-they collapse. The FDA found that with three generic makers, prices fall to just 42% of the brand’s original cost. That’s a 27% drop from the second entrant. In some cases, the price drops even lower-down to 30 cents per pill for common drugs like metformin or lisinopril. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening right now in markets where multiple companies are approved to make the same drug. Why does this happen? Because each new entrant doesn’t just add supply-they create a bidding war. Generic manufacturers operate on razor-thin margins. They don’t make money by charging more; they make it by selling volume. So when a third company shows up, they’ll undercut the others just to get shelf space. The second company responds. The first scrambles. And patients win.What happens when competition stalls

But not all generic markets work this way. Nearly half of all generic drugs in the U.S. are sold by only two manufacturers. That’s called a duopoly. And in those markets, prices don’t fall-they stabilize, or worse, rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida found that when competition drops from three makers to two, prices can jump 100% to 300%. Why? Because with only two players, they can quietly coordinate pricing without getting caught. No one’s left to challenge the price. No one’s forced to undercut. The market becomes a game of chicken-and patients pay the price. This isn’t random. It’s structural. When a market has only two manufacturers, they’re not competing-they’re coexisting. And that’s exactly what brand-name drug companies want. Some even pay generic makers to delay entering the market. These "pay-for-delay" deals cost patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs, according to the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association.

Who’s really controlling the price?

You might think more generic makers means lower prices for everyone. But the story gets messy when you look at who’s buying. Most prescriptions are handled by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like Express Scripts and CVS Health, and three giant wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-control 85% of the market. These middlemen negotiate bulk deals with manufacturers, and they often don’t pass savings on to patients. Here’s the catch: the FDA found that while manufacturer prices (what companies charge wholesalers) drop by 60-70% with multiple generics, what pharmacies actually pay-after wholesalers add their markup-is only down 40-50%. That gap? It’s not the manufacturers’ fault. It’s the supply chain. PBMs and wholesalers keep a big slice of the savings, even when generics compete fiercely. That’s why a $5.80 pill might still cost you $20 at the pharmacy counter. Insurance doesn’t always cover the full discount. Cash-paying patients get hit hardest. The real savings go to insurers and big pharmacy chains-not always to the person holding the prescription.Why more generics aren’t always coming

You’d think with so much money to be saved, more companies would rush in. But barriers are growing. Making a generic drug isn’t cheap. For complex pills-like extended-release versions or injectables-the cost to develop and get FDA approval can hit $2 million. Small companies can’t afford that. So the market is shrinking. Big players like Teva and Viatris now dominate. They bought up smaller generic makers. That reduces the number of independent competitors. Fewer players means less pressure to cut prices. And when a company controls 20 different generic drugs, they can afford to hold prices steady on some to make up for losses on others. The FDA has tried to fix this. Their GDUFA III program, running from 2023 to 2027, is speeding up approvals for complex generics. The CREATES Act, passed in 2022, tries to stop brand companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples they need to test their products. And lawmakers are pushing bills to ban "pay-for-delay" deals. But progress is slow. In 2022, the FDA approved over 1,000 generic drugs. But only a fraction of those were for drugs where competition was already weak. The real wins-adding a third or fourth maker to a stagnant market-are still rare.

The real impact: 5 billion saved

Between 2018 and 2020, the FDA approved 2,400 new generic drugs. The result? $265 billion in savings for American patients and insurers. That’s not a guess. It’s an official estimate. And the biggest chunk of those savings came from markets where two or three generics competed. The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at HHS confirmed that markets with three or more generic manufacturers saw price drops of 70% or more after three years. That’s the sweet spot. One generic? Minor savings. Two? Good savings. Three or more? Game-changing savings. Compare that to brand-name drugs, where a single company controls pricing for years. A cancer drug might cost $10,000 a month. After generics enter, it can drop to $300. That’s not just affordable-it’s life-changing.What patients can do

You can’t control how many generic makers enter the market. But you can use the competition to your advantage.- Ask your pharmacist: "Are there multiple generic versions of this drug?" If yes, ask which one is cheapest.

- Use price comparison tools like GoodRx or Blink Health. They show real-time prices from different suppliers.

- If your prescription is expensive, ask your doctor if a generic alternative exists-even if you’ve been on the brand for years.

- Call your insurance company. Sometimes, switching to a different generic version lowers your copay.

The bottom line

The second and third generic drug makers aren’t just competitors-they’re the most powerful tool we have to make medicine affordable. Their entry doesn’t just lower prices. It breaks monopolies, forces transparency, and gives patients real power. But that power only works if enough companies are allowed to enter the market. Right now, too many markets are stuck with just two players. Too many deals are being made behind closed doors. Too many patients are paying more than they should. The system works-when it’s allowed to work. And the data is clear: more competition means lower prices. Always.Why do generic drug prices keep dropping after the first one enters?

The first generic drug maker often sets a price that’s still higher than what the market can sustain because there’s no competition. When a second manufacturer enters, they undercut the first to win business. The first responds by lowering their price. A third maker pushes it even lower. This bidding war drives prices down until manufacturers can’t afford to cut further without losing money. The biggest drops happen between the first and third entrants.

Is the cheapest generic always the best choice?

Yes, for most medications. All FDA-approved generics must contain the same active ingredient, dose, and strength as the brand-name drug. They’re required to be bioequivalent, meaning they work the same way in your body. The only differences are in inactive ingredients like fillers or coatings-which rarely affect how the drug works. The price difference comes from manufacturing costs and competition, not quality.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others even if they’re the same?

It’s usually about market structure. If only two companies make the drug, they may not compete aggressively on price. If there are five or more, prices drop sharply. Also, some manufacturers sell directly to pharmacies at lower rates, while others rely on wholesalers who add their own markup. Your pharmacy’s contract with the supplier also affects what you pay.

Do insurance plans always pass on generic savings to patients?

Not always. Many insurance plans have fixed copays-for example, $10 for any generic-no matter how low the actual price is. That means if the drug drops from $15 to $3, you still pay $10. Some plans adjust copays based on price, but many don’t. Always check your plan’s formulary or ask your pharmacist what you’ll actually pay.

What’s being done to encourage more generic competition?

The FDA is speeding up approvals for complex generics through its GDUFA III program. Laws like the CREATES Act prevent brand companies from blocking access to samples needed for testing. Congress is also pushing to ban "pay-for-delay" deals, where brand companies pay generics to stay out of the market. These steps aim to break up monopolies and get more manufacturers into the game.

astrid cook

27 Jan, 2026

Ugh, I can't believe people still think generics are 'just as good'. My cousin took a generic version of her thyroid med and ended up in the ER. The fillers are different, and your body notices. Don't let Big Pharma trick you into thinking this is about savings-it's about control.

Kirstin Santiago

29 Jan, 2026

It's wild how much the system is rigged, but also how much power patients actually have if they know where to look. I started using GoodRx last year after my insulin jumped to $400-even though it was a generic. Found the same pill for $12 at a local pharmacy 10 miles away. No insurance needed. Just took 10 minutes to check. Small wins matter.

Candice Hartley

30 Jan, 2026

This made me cry 😭 I used to skip my blood pressure meds because the copay was $50. Now I get lisinopril for $3. I didn’t even know there were 5 different generics. Thank you for explaining this so clearly.

Desaundrea Morton-Pusey

1 Feb, 2026

Of course the government wants more generics. More competition means less profit for the rich. This is just another socialist trick to destroy American healthcare. You think the FDA cares about you? They care about global supply chains and China.

Murphy Game

2 Feb, 2026

Ever wonder why the same 3 companies own 80% of the generic market? Teva, Viatris, Mylan-they’re all connected. The FDA approves 'new' generics but they're just rebranded versions from the same parent company. This isn't competition-it's a shell game. Pay-for-delay? More like pay-for-illusion.

John O'Brien

2 Feb, 2026

Bro, I used to pay $120 for metformin. Now I get it for $4 at Walmart. No joke. I asked my pharmacist if they were all the same-she laughed and said 'dude, they're all made in the same factory, just different labels.' I started switching every month to the cheapest one. Saved $1k a year. Do the math.

Kegan Powell

3 Feb, 2026

It’s not just about price-it’s about dignity. When you’re choosing between food and medicine, the system has already lost. But when a third company shows up and drops the price to 30 cents? That’s not economics. That’s justice. We’ve been taught to see healthcare as a commodity. But it’s not. It’s a human right. And competition? That’s the only thing keeping it alive.

April Williams

4 Feb, 2026

Why are you letting them control your health? You’re not even trying. If your insurance won’t cover the cheapest generic, switch insurers. If your doctor won’t prescribe it, fire them. If your pharmacy won’t tell you the prices, go to another one. Stop being passive. You’re not a patient-you’re a consumer. Act like it.

Harry Henderson

4 Feb, 2026

STOP COMPLAINING AND START SHOPPING. I got my antidepressant for $1.50 at Costco. Not $15. Not $20. $1.50. I didn’t wait for someone to fix the system-I fixed it myself. Go to GoodRx. Ask your pharmacist. Call 3 pharmacies. You have power. Use it.

suhail ahmed

5 Feb, 2026

In India, we call this 'pharma democracy'-when ten brands fight over one pill, the people win. Here, it feels like a monopoly masquerading as choice. But you know what? The same tools work everywhere. Ask. Compare. Switch. The system doesn’t change until you stop being polite and start being loud.

Andrew Clausen

6 Feb, 2026

Correction: The FDA does not state that prices fall to 42% of the brand price with three generics. The data cited is from a 2018 JAMA study, not an FDA publication. Additionally, the term 'collapse' is hyperbolic. Prices stabilize, not collapse. Precision matters when discussing public health policy.