Genetic Drug Metabolism Checker

How This Tool Works

Select a medication and your genetic variant status to see how it affects your body's processing of that drug. This tool is based on clinical guidelines from CPIC and PharmGKB.

What if the pill you take every day could make you sicker instead of better-just because of your genes? It’s not science fiction. For millions of people, the difference between a drug working or causing harm comes down to tiny changes in their DNA. This is pharmacogenomics-the science of how your genes control how your body handles medicine.

Why Your Genes Matter When You Take a Pill

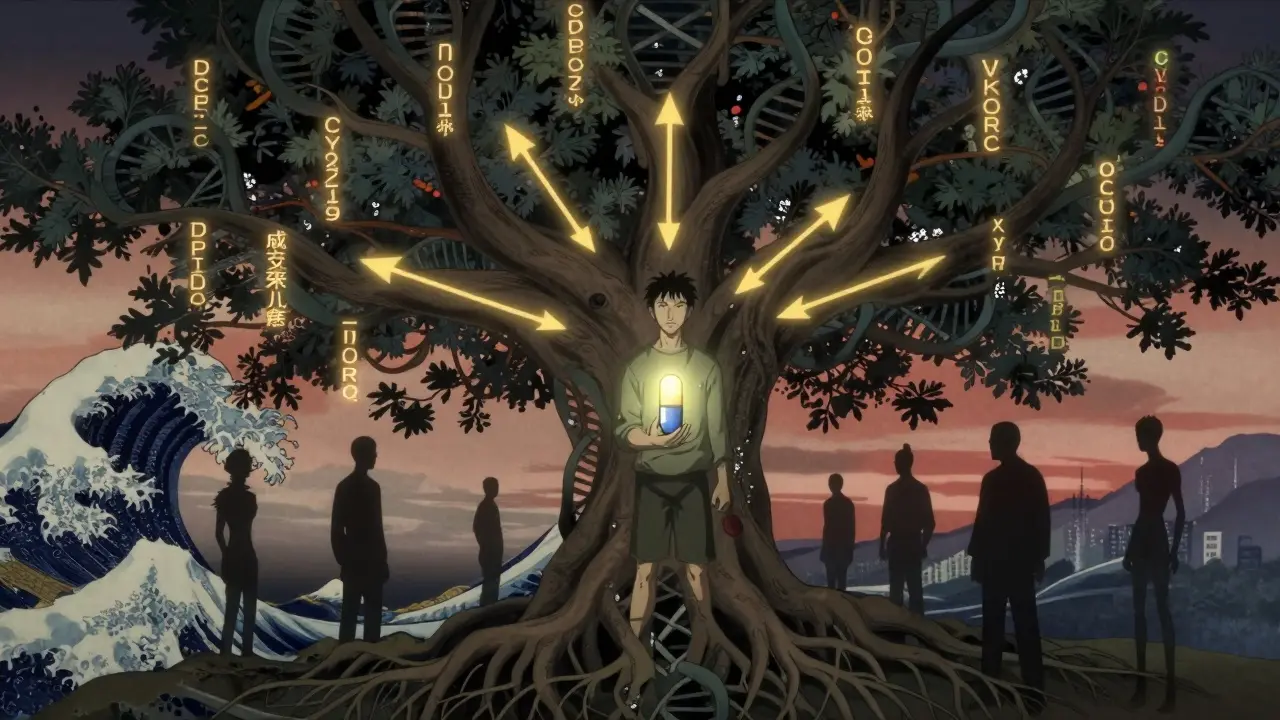

Most people think drugs work the same for everyone. But that’s not true. Two people can take the same dose of the same antidepressant, and one feels better while the other gets dizzy, nauseous, or worse. Why? Because their bodies process the drug differently. And that difference often comes from genes. Your body doesn’t just absorb medicine like a sponge. It breaks it down, moves it around, and gets rid of it. These steps are controlled by proteins made from your genes. If those genes have small changes-called variants or polymorphisms-the proteins can work too fast, too slow, or not at all. This changes how much of the drug stays in your system, how long it lasts, and whether it causes side effects. The biggest players in this game are enzymes in the liver, especially the cytochrome P450 family. These enzymes handle about 70-80% of all prescription drugs. Among them, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 are the most important. For example, CYP2D6 metabolizes 25% of common medications, including antidepressants like fluoxetine, beta-blockers like metoprolol, and painkillers like codeine. If you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, codeine won’t turn into its active form-and you won’t get pain relief. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, it turns into morphine too fast, and you could overdose even on a normal dose.Real-Life Examples: When Genes Save Lives

One of the clearest success stories is with the cancer drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). About 0.2% of people have a variant in the DPYD gene that makes them unable to break down this drug. Without testing, they can suffer severe, life-threatening toxicity-low blood counts, gut damage, even death. Testing for DPYD before treatment can prevent this. In the UK, hospitals now test all patients before giving 5-FU. Since doing so, serious side effects have dropped by more than half. Another example is warfarin, a blood thinner. Getting the dose right is tricky. Too little, and you risk clots. Too much, and you bleed. For years, doctors guessed the dose based on age, weight, and diet. Now, we know that two genes-CYP2C9 and VKORC1-explain most of the variation. People who get tested reach the right dose 2.3 days faster and have 31% fewer dangerous bleeds in the first month. That’s not just better outcomes-it’s fewer hospital visits, fewer emergencies, fewer deaths. In psychiatry, the impact is huge. About 40-60% of people don’t respond to their first antidepressant. Why? Often, it’s because their genes make them poor metabolizers of SSRIs like sertraline or escitalopram. A 2022 study in JAMA showed that when doctors used genetic testing to choose antidepressants, remission rates jumped from 39% to 66%. Side effects dropped by nearly 30%. One patient on Reddit wrote: “After 8 years of failed meds, my CYP2D6 test showed I was a poor metabolizer. Switching to bupropion changed my life.”The Dark Side: When Testing Isn’t Enough

Pharmacogenomics sounds perfect, but it’s not magic. For many drugs, genetics only tell part of the story. If a drug is cleared by multiple pathways-say, through the liver, kidneys, and gut-then one gene variant won’t make a big difference. That’s why PGx doesn’t help much for drugs like ibuprofen or acetaminophen. They’re safe for almost everyone, regardless of genes. Another problem? The research is mostly done on people of European descent. About 90% of pharmacogenomic studies use data from white populations. But gene variants that matter in one group may be rare or absent in others. For example, the CYP2C19 variant that makes clopidogrel (a heart drug) ineffective is found in 30% of East Asians but only 15% of Europeans. If we only test based on European data, we miss risks in other groups. This isn’t just unfair-it’s dangerous. A 2023 study in Nature Genetics called it a “genomic equity crisis.” Cost and access are also big barriers. A full pharmacogenomic panel costs $250-$500 in the U.S. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. A 2022 survey found 18% of patients had their tests denied outright. Even when covered, getting prior authorization can take two weeks or more. For someone in acute pain or depression, that delay matters.

Who Benefits Most Right Now?

Not everyone needs a genetic test before taking medicine. But for some groups, it’s life-changing:- People starting antidepressants-if you’ve tried two or more without success, testing can point you to one that actually works.

- Cancer patients-especially those getting 5-FU, thiopurines (like azathioprine), or certain chemotherapy drugs.

- Patients on blood thinners-warfarin users benefit most from CYP2C9 and VKORC1 testing.

- People with heart disease-clopidogrel doesn’t work well in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers, who are at higher risk for heart attacks.

- Those on strong painkillers-codeine, tramadol, and oxycodone are all affected by CYP2D6 status.

How It Works in Practice

Getting tested is easier than ever. Many hospitals now offer pre-emptive testing-meaning you get screened once, and your results are stored in your medical record. Then, anytime a doctor prescribes a drug that interacts with your genes, the system flags it automatically. The process usually looks like this:- You give a saliva sample or a cheek swab.

- The lab tests 50-100 genes linked to drug metabolism.

- Your results come back in 1-2 weeks, showing if you’re a poor, intermediate, normal, or ultra-rapid metabolizer for each enzyme.

- Your doctor or pharmacist gets a report with clear recommendations: “Avoid drug X,” “Use half dose of drug Y,” or “Drug Z is preferred.”

The Future: Will Everyone Get Tested?

Right now, pharmacogenomics is still mostly used in big hospitals and academic centers. But things are changing fast. The FDA approved its first next-generation PGx test in January 2023-one that checks 27 genes and 350+ medications. The NIH just launched a $190 million project to expand testing in diverse populations. The VA has already tested over 100,000 veterans-and saw 22% fewer hospitalizations. By 2030, Deloitte predicts most people will have their pharmacogenomic profile done by age 18. Imagine getting your DNA tested at 16, and your doctor has your report on file before you ever need antibiotics, painkillers, or antidepressants. No more trial and error. No more dangerous side effects. Just the right drug, at the right dose, from day one. But we’re not there yet. Until reimbursement improves, until testing becomes affordable for everyone, and until we fix the racial bias in the data, pharmacogenomics will remain a tool for some-not a standard for all.What You Can Do Today

If you’ve had bad reactions to meds, or if you’ve tried several drugs without success, ask your doctor about pharmacogenomic testing. You don’t need to wait for a specialist. Many primary care doctors now work with pharmacists who can interpret results. If you’ve already done a direct-to-consumer test like 23andMe, check if they include pharmacogenomics. They report on 7 drugs, including clopidogrel and simvastatin. It’s not a full panel, but it’s a start. And if you’re a healthcare provider: learn the basics. You don’t need to be a geneticist. Just know which drugs have strong gene links-and when to refer. The CPIC guidelines are free. The data is out there. The tools are ready. This isn’t about replacing good clinical judgment. It’s about making it better. Your genes don’t define you-but they can tell you which medicine will help, not hurt. And that’s powerful.What is pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect how your body responds to medications. It combines genetics and pharmacology to predict whether a drug will work for you, how much you need, and whether you’re at risk for side effects. It’s not about predicting disease-it’s about personalizing treatment.

Which genes are most important for drug metabolism?

The most important genes are those that code for drug-metabolizing enzymes, especially in the cytochrome P450 family: CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4. These handle about 70-80% of all prescription drugs. Other key genes include DPYD (for cancer drugs), TPMT (for immune suppressants), and SLCO1B1 (for statins like simvastatin).

Does pharmacogenomics testing work for all drugs?

No. It works best for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-where small changes in dose can cause harm or fail to help. Examples include antidepressants, blood thinners, chemotherapy, and certain painkillers. For drugs like ibuprofen or amoxicillin, which are safe for most people, genetics don’t matter much.

Is pharmacogenomics testing covered by insurance?

Coverage is growing but inconsistent. As of 2023, 87% of Medicare Advantage plans and 65% of commercial insurers cover at least one pharmacogenomic test-usually for high-risk drugs like clopidogrel or 5-FU. But many tests still require prior authorization, and some are denied. Always check with your insurer before testing.

Can I use my 23andMe results for pharmacogenomics?

Yes, but with limits. 23andMe reports on 7 medications, including clopidogrel, simvastatin, and codeine. It’s a good starting point, but it only covers a small fraction of the genes that matter. For full clinical use, a lab-ordered test that analyzes 50-100 genes is recommended.

Why is there a lack of diversity in pharmacogenomics research?

Over 90% of pharmacogenomic studies have used data from people of European ancestry. This means gene variants common in African, Asian, or Indigenous populations are often missed. As a result, tests and guidelines may not work as well for non-European patients. New research initiatives are now focused on fixing this gap, but it’s still a major barrier to equitable care.

Annette Robinson

7 Jan, 2026

I’ve seen this firsthand with my mom-she was on three different antidepressants over five years, each one making her sicker than before. When she finally got tested, it turned out she was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Switching to bupropion was like turning on a light after living in a basement for a decade. No more brain fog, no more nausea. Just… peace. I wish every doctor did this before prescribing.

Luke Crump

9 Jan, 2026

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me our entire medical system is built on the assumption that we’re all the same biological robot? That’s not science. That’s colonial thinking dressed in lab coats. We’re not widgets on an assembly line. Your DNA isn’t a bug-it’s a feature. And if your doctor still prescribes codeine like it’s aspirin? They’re not just outdated-they’re dangerous.

Manish Kumar

9 Jan, 2026

You know, in India, we’ve been dealing with this for decades without fancy genetic tests. My uncle took warfarin for years, and his doctor just watched his INR like a hawk-every week, no exceptions. He didn’t need a $500 panel to know his body was different. We adapted through observation, patience, and trust in the doctor-patient bond. Technology helps, yes-but it shouldn’t replace human judgment. Sometimes, the simplest solution is the most sustainable one.

Prakash Sharma

11 Jan, 2026

Why should Indians pay for American research that ignores our genetics? You talk about CYP2C19 variants being common in Asia-but your studies still use European data to make guidelines. That’s not progress. That’s exploitation. We have our own population data, our own variants, our own history. Why are we still waiting for Western labs to validate what we’ve seen in our clinics for years? It’s time India leads this conversation-not follows.

Donny Airlangga

12 Jan, 2026

My sister was misdiagnosed with anxiety because her SSRIs made her suicidal. Turns out she’s a CYP2C19 ultra-rapid metabolizer. Once they switched her to venlafaxine, everything changed. I wish this was standard. Not because it’s cool tech, but because people shouldn’t have to suffer for years just because doctors don’t ask the right questions.

Kristina Felixita

14 Jan, 2026

OMG YES!! I did 23andMe and it flagged me as a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer!! I was on sertraline for 3 years and felt like a zombie!! switched to bupropion and now I can actually enjoy coffee again?? like… i forgot what it felt like to be awake?? thank you for this post!!

Joanna Brancewicz

15 Jan, 2026

CYP2D6, CYP2C19, DPYD, VKORC1-these are the critical pharmacogenomic loci. Clinical actionability is highest for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices. Testing reduces adverse events by 30–50% in high-risk cohorts. Implementation is feasible via EHR integration and CPIC guidelines. Cost-benefit analysis favors preemptive testing in high-utilizer populations.

Lois Li

16 Jan, 2026

I work in a rural clinic. We don’t have genetic testing. But we listen. We watch. We adjust. One patient said, ‘Every pill I take makes me feel like I’m dying.’ We stopped everything, started slow, tried one at a time. Found the culprit within weeks. Genetics matter-but so does patience. So does care. So does showing up. Not every solution needs a lab.

christy lianto

18 Jan, 2026

THIS IS THE FUTURE. And it’s not coming-it’s already here. I was one of those people who tried six antidepressants and ended up in the ER. Now I have my profile on file. Every time I get a new script, my pharmacist says, ‘This one’s safe.’ No more guessing. No more suffering. We need this everywhere. Not just for the rich. For everyone.

Ken Porter

19 Jan, 2026

Genetic testing? Sounds like another way to make healthcare more expensive. We’ve been prescribing meds for 100 years without DNA reports. Why fix what ain’t broke? Plus, most people don’t even know what a SNP is. This is tech hype wrapped in medical jargon. Stick to the basics: dose, monitor, adjust.

swati Thounaojam

19 Jan, 2026

My dad took clopidogrel after stent… had a heart attack 2 weeks later. Turned out he was CYP2C19 poor metabolizer. Doctor never tested. We’re lucky he survived. Now I tell everyone: ask for the test. Don’t wait till it’s too late.