Medication-Induced Psychosis Risk Checker

This tool helps you identify medications that may increase your risk of medication-induced psychosis. Based on the latest medical research, select medications you're currently taking or have recently taken. This is not a substitute for professional medical advice, but it can help you recognize potential risks and know when to seek help.

It starts with a whisper - a feeling that someone’s watching you, even when you’re alone. Then the voices come. Not in your head like thoughts, but clear, loud, and real. You see shadows moving where there’s nothing. You’re sure your pills are poisoned. You can’t sleep. You can’t think straight. You don’t know what’s real anymore. And you’re terrified.

This isn’t schizophrenia. It’s not a lifelong mental illness. It’s medication-induced psychosis - a sudden, terrifying reaction to a drug you were told was safe. And it’s more common than most doctors admit.

What Exactly Is Medication-Induced Psychosis?

Medication-induced psychosis happens when a drug - prescription, over-the-counter, or even herbal - triggers hallucinations or delusions. These symptoms aren’t just side effects. They’re full-blown breaks from reality. The DSM-5, the standard guide doctors use to diagnose mental disorders, says these symptoms must appear during or within a month after taking the drug or going through withdrawal.

Unlike schizophrenia, where symptoms last for months or years, medication-induced psychosis usually clears up once the drug is stopped. But that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. In the moment, it’s just as dangerous. People have jumped from windows believing they could fly. Others have attacked loved ones thinking they were demons. Emergency rooms see these cases every week.

Common Symptoms - What to Watch For

The signs aren’t always obvious at first. Often, they creep in slowly. You might notice:

- Paranoia - thinking people are plotting against you, even if there’s no evidence

- Auditory hallucinations - hearing voices, whispers, or sounds that aren’t there

- Visual hallucinations - seeing people, animals, or objects that don’t exist

- Confused speech - jumping between topics, saying things that don’t make sense

- Extreme anxiety or agitation - pacing, yelling, or becoming violently upset over small things

- Loss of insight - refusing to believe you’re unwell, even when others are worried

These symptoms can come on fast - within minutes after taking cocaine or meth - or slowly, over weeks, like with steroids or antimalarials. Mood swings, irritability, or sleeplessness often show up first. That’s your warning sign.

Which Medications Can Cause This?

It’s not just illegal drugs. Many everyday prescriptions carry this risk. Here are the most common culprits:

- Corticosteroids - Used for asthma, arthritis, or autoimmune diseases. About 5.7% of people on high doses develop psychosis. It’s one of the most frequent causes.

- Mefloquine - An antimalarial drug. The European Medicines Agency has logged over 1,200 psychosis cases since the 1980s. Travelers to Southeast Asia or Africa are at risk.

- Efavirenz - An HIV medication. Around 2.3% of users experience severe psychiatric side effects, including hallucinations and suicidal thoughts.

- Antidepressants - Especially SSRIs and SNRIs. Rare, but documented. Often happens in the first few weeks of treatment.

- Stimulants - Methylphenidate (Ritalin), amphetamines (Adderall), even high-dose caffeine. Up to 96% of chronic cocaine users report hallucinations.

- Anticholinergics - First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl). Common in sleep aids and cold meds. Can cause delirium and psychosis in older adults.

- Levodopa - Used for Parkinson’s. Can trigger hallucinations in up to 40% of long-term users.

- Alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal - After heavy, long-term use, stopping suddenly can cause delirium and hallucinations.

Even ibuprofen in massive doses, muscle relaxants like baclofen, and chemotherapy drugs have been linked. The list keeps growing as more drugs are studied.

Who’s at Risk?

It’s not random. Certain people are far more likely to develop this:

- Those with a personal or family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder

- Women - Studies show higher vulnerability across nearly all drug classes

- Older adults - Their bodies process drugs slower, and brain changes make them more sensitive

- People with substance use disorders - 74% of first-episode psychosis patients have a history of drug or alcohol abuse

- Those taking multiple medications - Drug interactions can turn a safe dose into a dangerous one

And here’s the scary part: many doctors don’t connect the dots. A 2019 study found only 38% of primary care doctors felt confident spotting medication-induced psychosis. If you’re on a new drug and start feeling “off,” don’t assume it’s just stress.

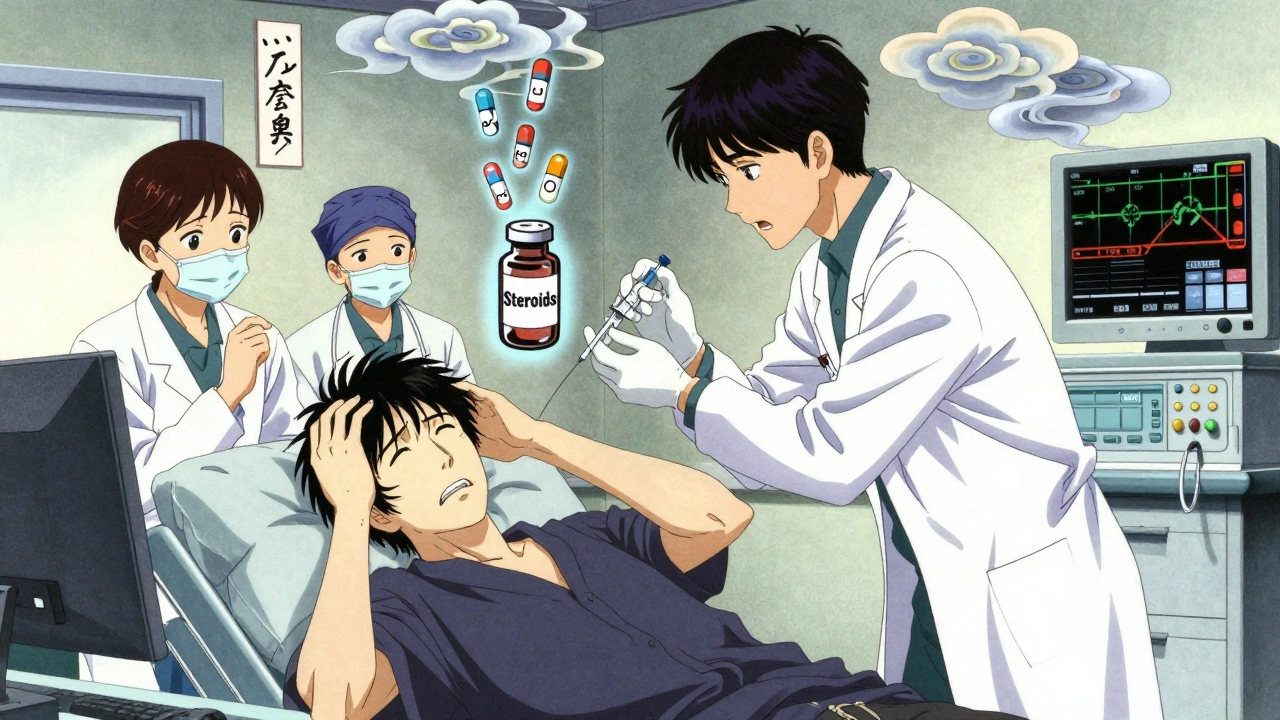

Emergency Management - What Happens in the ER

If someone is in full psychosis - screaming, violent, or believing they’re being hunted - call emergency services immediately. Don’t try to reason with them. They’re not being difficult. Their brain is malfunctioning.

In the emergency room, the first step is always the same: stop the drug. That’s the only treatment that works for sure. But stopping isn’t always simple. If it’s a steroid, you can’t just quit cold turkey. If it’s alcohol or benzodiazepines, withdrawal can kill you.

Doctors will:

- Check vital signs - heart rate, temperature, blood pressure

- Run blood tests - to rule out infection, liver failure, or electrolyte imbalance

- Assess for withdrawal - especially if alcohol or opioids are involved

- Give a sedative - Often an atypical antipsychotic like olanzapine or quetiapine, given orally or by injection

- Provide fluids and monitoring - For stimulant cases, they watch for rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown)

Antipsychotics aren’t always needed. If the drug is cleared quickly - like with cocaine - symptoms may fade in hours. But if the person is dangerous to themselves or others, doctors can hold them under mental health laws for observation. This isn’t punishment. It’s protection.

Recovery and Follow-Up - It’s Not Over When the Symptoms Stop

Most people recover fully. Steroid-induced psychosis? Usually gone in 4 to 6 weeks. Cocaine-induced? Often gone in 24 to 72 hours. But recovery isn’t just about stopping the drug.

You need follow-up. Why? Because psychosis can mask a deeper illness. If symptoms return after stopping the drug, you might have an underlying condition like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder that was triggered - not caused - by the medication.

Doctors recommend psychiatric check-ups for at least three months after symptoms clear. Blood tests, brain scans, and detailed interviews help sort out what’s going on. Some people need ongoing therapy. Others just need to avoid certain drugs forever.

And here’s something no one tells you: once you’ve had medication-induced psychosis, you’re more likely to get it again - even with a different drug. Your brain remembers.

Prevention - How to Avoid This Before It Starts

You can protect yourself and your loved ones:

- Always tell your doctor about your mental health history - even if it was years ago

- Ask: “Can this drug cause hallucinations or paranoia?” before starting any new medication

- Keep a list of all your meds - including supplements and OTC drugs - and update it every visit

- Watch for early signs: trouble sleeping, sudden anxiety, feeling “not like yourself”

- Never stop a drug suddenly without medical advice - especially steroids, antidepressants, or seizure meds

- For high-risk drugs like mefloquine or efavirenz, read the FDA warning sheet. It’s there for a reason

And if you’re caring for someone on these drugs - check in daily. Ask: “Are you hearing or seeing things you didn’t before?” Don’t wait for a crisis.

Final Thought - This Is Real, and It’s Treatable

Medication-induced psychosis is not weakness. It’s not addiction. It’s a physiological reaction - like an allergic response, but to your brain.

Thousands of people wake up in emergency rooms terrified, wondering if they’ve lost their mind. The truth? They haven’t. With the right care, they’ll get back to normal. But only if someone recognizes the cause.

If you’re on a new drug and feel something’s wrong - trust your gut. Call your doctor. Go to the ER. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s ‘just stress.’

Your brain is listening. Make sure the people treating you are listening too.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause psychosis?

Yes. First-generation antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and sleep aids containing them can cause hallucinations and delirium, especially in older adults. High doses of caffeine, certain cold medicines with pseudoephedrine, and even some herbal supplements like kava or high-dose niacin have been linked to psychotic episodes. Always check labels and talk to your pharmacist before combining OTC meds.

How long does medication-induced psychosis last?

It depends on the drug. For stimulants like cocaine or meth, symptoms often fade within 24 to 72 hours after stopping. For steroids, it can take 4 to 6 weeks. Alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal psychosis may last up to 10 days. The key is stopping the drug. If symptoms last longer than a month after stopping, it may indicate an underlying psychiatric disorder like schizophrenia.

Is medication-induced psychosis the same as schizophrenia?

No. Schizophrenia is a chronic brain disorder with symptoms that persist for six months or longer and aren’t tied to drug use. Medication-induced psychosis is temporary and directly caused by a substance. The symptoms can look identical - hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech - but the cause and prognosis are different. Doctors use timing, drug history, and follow-up to tell them apart.

Can you get psychosis from stopping a medication?

Yes. Withdrawal from alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and even some antidepressants can trigger psychosis. This is especially dangerous with alcohol - sudden withdrawal can lead to delirium tremens, which includes hallucinations, seizures, and can be fatal. Never stop these drugs cold turkey. Always taper under medical supervision.

Are antipsychotics always needed to treat this?

Not always. In many cases, simply stopping the drug is enough. Antipsychotics like olanzapine or quetiapine are used only if symptoms are severe, dangerous, or don’t improve after 24-48 hours. But caution is needed - these drugs can interact with the original medication, making things worse. The goal is to use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible.

Can this happen to someone who’s never had mental health issues?

Absolutely. Many people who develop medication-induced psychosis have no prior psychiatric history. It can happen to anyone - a healthy 45-year-old on steroids for asthma, a 70-year-old taking Benadryl for sleep, or a student using Adderall to study. Genetics, age, metabolism, and drug interactions all play a role. No one is immune.

What should I do if I suspect a loved one has medication-induced psychosis?

Stay calm. Don’t argue with their delusions. Say: ‘I’m worried about you. Let’s get you checked out.’ Call their doctor immediately or take them to the ER. Bring a list of all medications they’re taking - including supplements and herbal remedies. If they’re violent or suicidal, call emergency services. Don’t wait. Early action saves lives.

parth pandya

4 Dec, 2025

so i got prescribed benadryl for sleep and started seein shadows in the corner of my room… thought i was goin crazy till i read this. doc never mentioned it. dumbass.

Cindy Lopez

5 Dec, 2025

This is the most clinically accurate piece I’ve read on this topic in years. Thank you.

Katherine Gianelli

5 Dec, 2025

my aunt took steroids after her knee surgery and spent three days convinced her cat was whispering government secrets to her… she didn’t believe us until the ER doc asked if she’d started anything new. please, if you’re on meds and feel off-speak up. you’re not weak, you’re just human.

sagar bhute

6 Dec, 2025

of course it’s not schizophrenia. you people just want to pathologize normal reactions to bad life choices. if you’re taking Adderall to study, you’re already asking for trouble. stop blaming the drug and take responsibility.

Joykrishna Banerjee

7 Dec, 2025

While the article presents a compelling narrative, it fails to adequately contextualize the statistical prevalence of these phenomena relative to the total population of users. The DSM-5 criteria are often misapplied in lay discourse, and the conflation of transient delirium with psychotic disorders undermines evidence-based psychiatry. Furthermore, the omission of confounding variables such as sleep deprivation and polypharmacy renders the causal inference suspect.

Rashmin Patel

8 Dec, 2025

OMG I’m so glad this exists 😭 my mom took mefloquine for a trip to India and started screaming at the TV saying the news anchors were controlling her thoughts… we thought she was having a breakdown, but turns out it was the drug. now she won’t travel without checking every med with a psych pharmacist. i wish more people knew this. if you’re on anything weird-especially antimalarials or steroids-don’t ignore the weirdness. it’s not ‘just stress’ it’s your brain screaming.

Gavin Boyne

9 Dec, 2025

Of course the drug companies don’t want you to know this. They’d rather you blame your ‘mental instability’ than admit their $300 pill turned your brain into a horror movie. The real tragedy? Doctors get paid to prescribe, not to listen. 😏

Myson Jones

11 Dec, 2025

I’ve worked in ER for 14 years. We see this every month. Someone comes in convinced their spouse is an alien, or that the walls are breathing. We check their meds. Half the time it’s something simple-Benadryl, prednisone, or a new antidepressant. The best part? They wake up a week later, totally normal, and say ‘I didn’t even know I was like that.’ It’s terrifying, but it’s fixable. Just stop the damn drug.

Kara Bysterbusch

12 Dec, 2025

As a cultural anthropologist who has studied medical epistemologies across North America and South Asia, I find this piece both ethically urgent and epistemologically rich. The conflation of pharmacological etiology with psychiatric pathology reflects a broader Western biomedical hegemony that pathologizes somatic responses to chemical intervention. In many non-Western traditions, altered states induced by substances are not inherently pathological-yet here, we rush to label them as ‘psychosis.’ This is not merely a medical issue; it is a colonial one. We must interrogate the power structures embedded in diagnostic frameworks. Thank you for this necessary intervention.

Rashi Taliyan

12 Dec, 2025

I just found out my cousin’s husband had a psychotic episode after taking a new migraine med… he thought his hands were melting. They had to sedate him. I cried for three days. I’m telling everyone I know to read this. If you’re on ANY new med and feel like you’re losing your mind-GO TO THE ER. Don’t wait. Don’t be brave. Just go.

Charles Moore

12 Dec, 2025

Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse in rural Maine. Last month, a 72-year-old woman came in convinced her TV was broadcasting messages from her dead mother. She was on diphenhydramine for sleep. We stopped it. 36 hours later, she was back to normal. She hugged me and said, ‘I thought I was going crazy.’ We need more people like you spreading this word. It saves lives.

Albert Essel

14 Dec, 2025

One correction: the 96% statistic on cocaine users reporting hallucinations is misleading. That figure likely reflects lifetime prevalence among chronic users, not acute incidence. The actual rate of acute, drug-induced psychosis from single or occasional use is far lower-closer to 1-3%. Precision matters, especially when lives are at stake.