When a product leaves a factory, no one should get sick from it. That’s the baseline. But how do you make sure that doesn’t happen? In food plants, pharmaceutical labs, and cosmetic factories, the answer isn’t just about cleaning surfaces-it’s about environmental monitoring. It’s not optional. It’s not a checkbox. It’s the line between a safe product and a recall that costs millions-and worse, lives.

Why Environmental Monitoring Isn’t Just Good Practice

Think of your factory like a house. You don’t wait for a mouse to show up before you check the basement. You look for signs before the problem gets big. Environmental monitoring works the same way. It’s not about finding contamination after it’s already in your product. It’s about finding where it could come from-before it gets there. The CDC says it clearly: environmental sampling helps you confirm the presence of a hazard and prove you’ve removed it. In food manufacturing, Listeria monocytogenes can hide in drains, under equipment, even on overhead pipes. One outbreak linked to contaminated deli meats in 2022 cost over $150 million in recalls and lawsuits. In pharma, a single fungal spore in a sterile vial can ruin a batch worth $500,000. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’re real, documented, and preventable.The Zone System: How to Know Where to Look

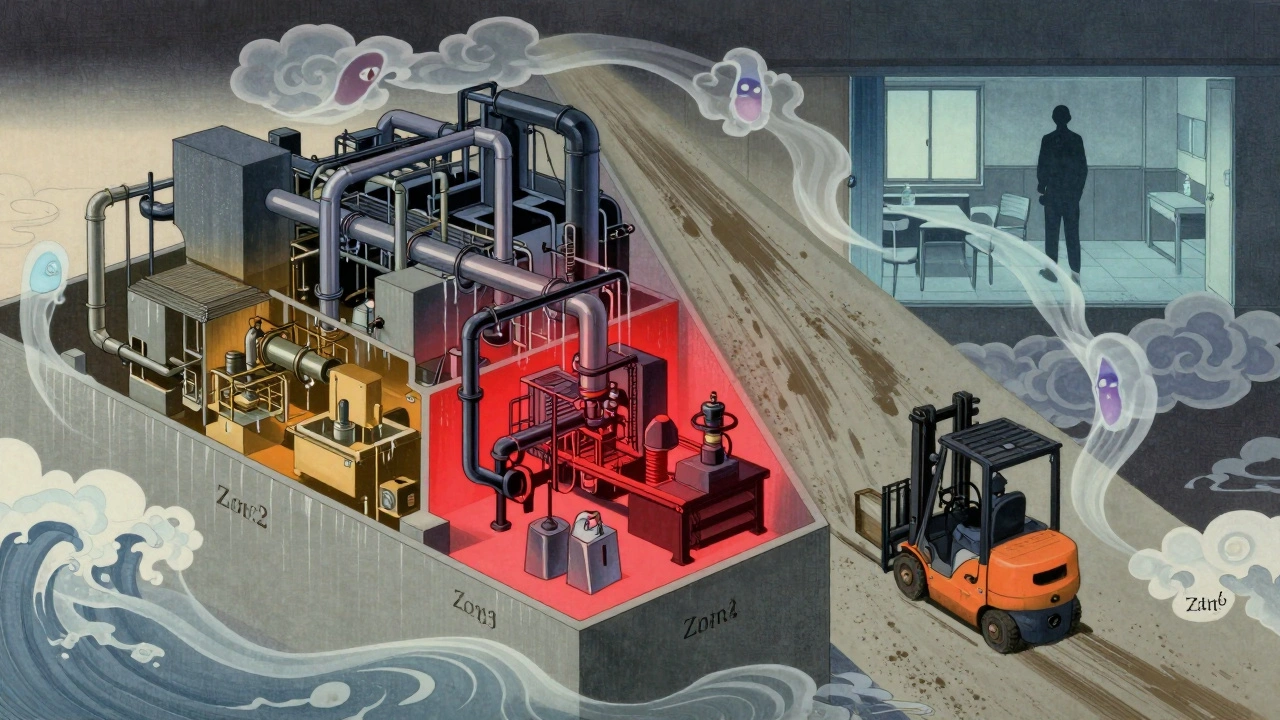

Every facility uses a zone-based approach. It’s simple, universal, and it works. Here’s how it breaks down:- Zone 1: Direct food or product contact surfaces. Think slicers, mixers, filling nozzles, conveyor belts. These are your highest risk. If something’s wrong here, it goes straight into the product.

- Zone 2: Surfaces near food contact areas. Equipment housings, refrigeration units, nearby walls. Contamination here can splash, drift, or get carried in by air.

- Zone 3: Remote areas close to production. Forklifts, carts, floor drains, utility lines. Surprising? Yes. A PPD Labs study found that 62% of all contamination events came from Zone 3 and 4 surfaces-not Zone 1.

- Zone 4: Outside the production area. Break rooms, offices, hallways. Still monitored, but less frequently. These are your early warning system.

What You’re Testing For-and How

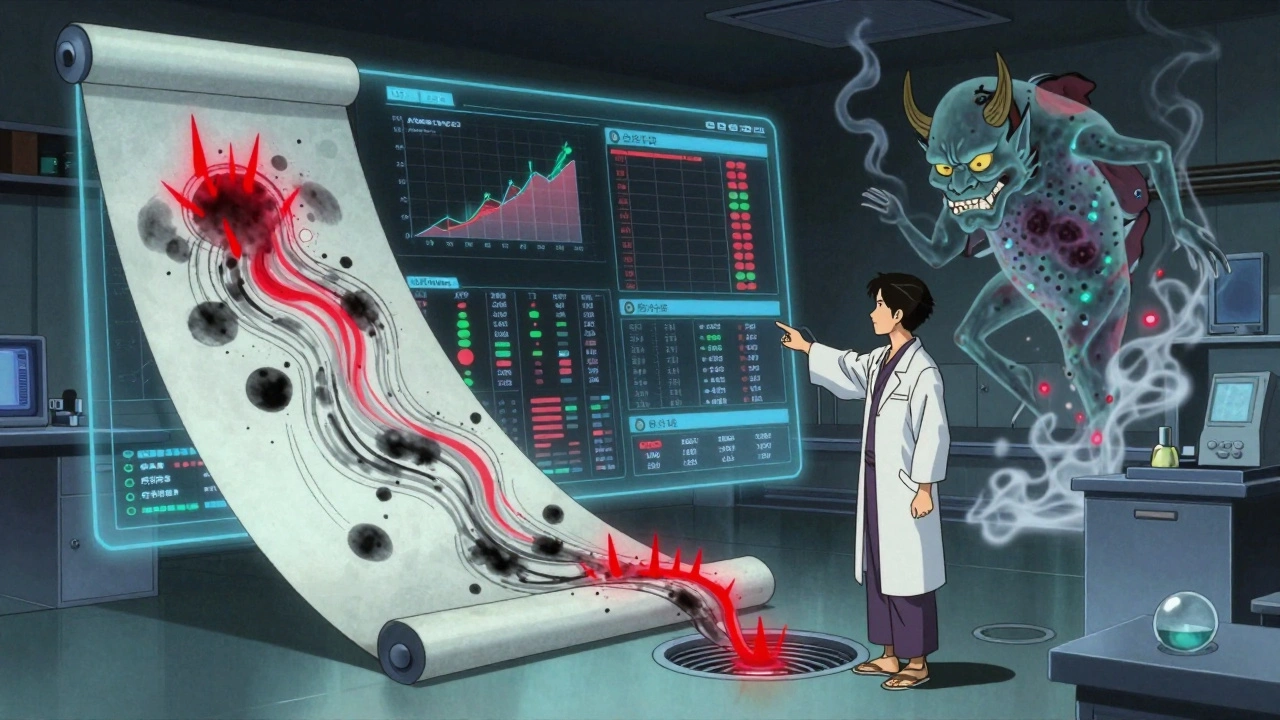

You don’t test for everything. You test for what matters. Here’s what’s tracked in regulated industries:- Microbes: Bacteria, mold, yeast. Listeria, Salmonella, and E. coli are the big targets in food. In pharma, it’s total viable count and specific pathogens like Aspergillus.

- Particulates: Dust, fibers, skin flakes. Critical in sterile drug manufacturing. FDA requires continuous monitoring in ISO Class 5 cleanrooms.

- Chemicals: Residues from cleaning agents, lubricants, or heavy metals. ICP (Inductively Coupled Plasma) testing detects lead, mercury, or nickel traces.

- Water quality: For pharmaceuticals, purified water must meet USP <645> standards. Conductivity and TOC (Total Organic Carbon) are measured daily.

How Often Should You Sample?

Frequency isn’t arbitrary. It’s risk-based.- Zone 1: Daily to weekly. RTE (Ready-to-Eat) food plants must test for Listeria weekly under USDA’s Listeria Rule.

- Zone 2: Weekly to monthly. If a machine runs 24/7, test after each cleaning cycle.

- Zone 3: Monthly. But if you’ve had a past event here-like a floor drain contamination-up the frequency.

- Zone 4: Quarterly. Still important. A contaminated forklift tire can track Listeria into Zone 1.

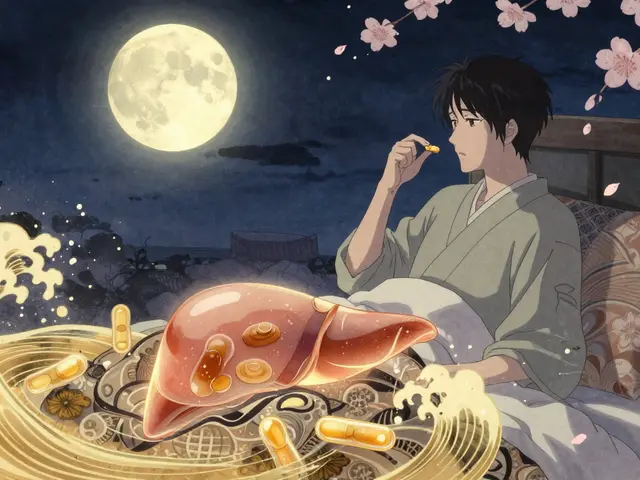

ATP Testing: The Fast Way to Check Cleanliness

Traditional microbiology takes 24-72 hours. That’s too slow. You can’t wait three days to know if a surface is clean before running the next batch. ATP (adenosine triphosphate) testing gives you results in seconds. It measures organic residue-anything alive or recently alive. It’s not a replacement for microbial tests. It’s a quick check. Think of it like a smoke alarm. It doesn’t tell you if there’s a fire, but it tells you something’s burning. FDA data shows facilities using ATP testing cut turnaround time between production runs by 32%. That’s faster scheduling, less downtime, less waste. But here’s the catch: ATP doesn’t tell you if it’s Listeria. It just tells you there’s residue. You still need microbial testing for compliance. Use ATP for daily sanitation checks. Use swabs for regulatory proof.The Hidden Problem: Data That Doesn’t Talk to Each Other

Most facilities have three sets of data:- ATP results

- Microbial culture results

- Allergen swab tests

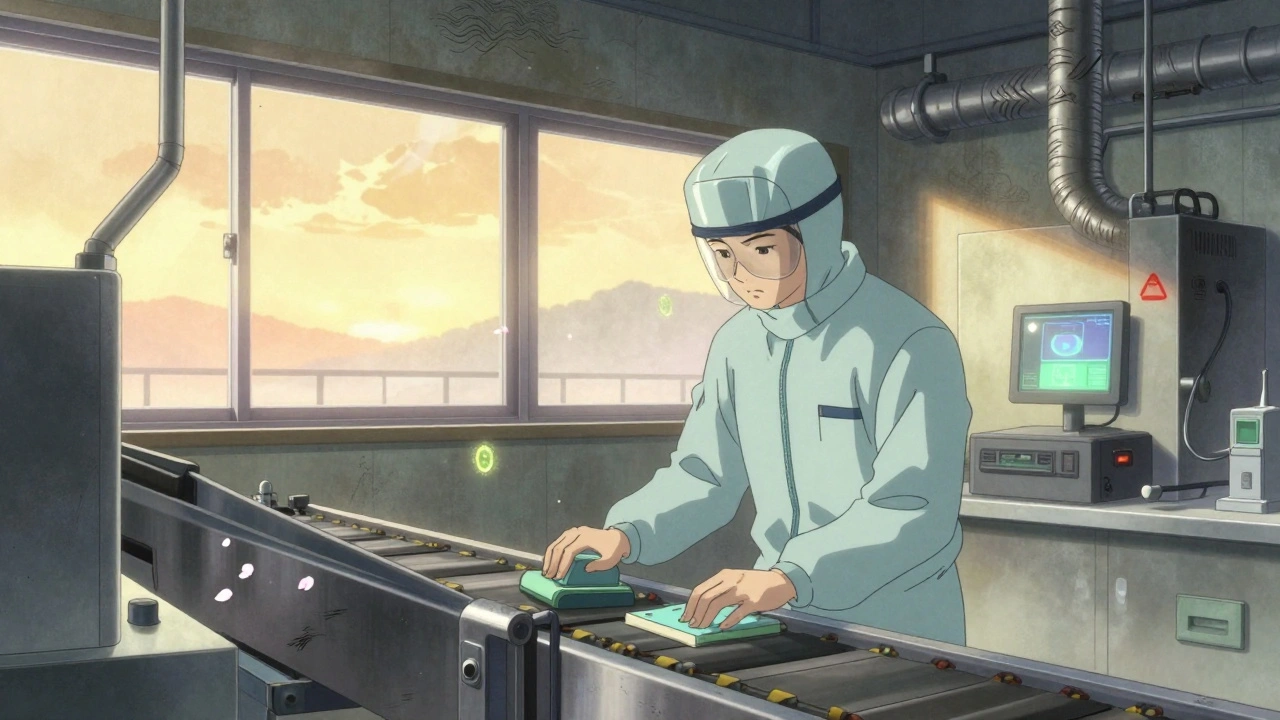

Training and Compliance: The Real Bottleneck

You can have the best equipment, the best software, the best zone map. If your technician doesn’t know how to swab properly, it’s all useless. FDA guidelines say: environmental sampling staff need at least 40 hours of hands-on training before they can collect official samples. That includes:- How to sterilize samplers

- How to avoid cross-contamination

- How to label samples correctly

- How to document deviations

What’s Changing in 2025?

Regulations aren’t standing still. The EU’s Annex 1 update in 2023 requires real-time data trending for critical parameters. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance pushes for rapid methods like next-generation sequencing (NGS). That means:- Identifying pathogens in under 24 hours instead of 72

- Spotting antimicrobial-resistant strains in environmental samples

- Using AI to predict contamination hotspots before they happen

How Much Does This Cost?

A medium-sized food plant spends $15,000-$25,000 a year on testing supplies, lab fees, and training. That sounds high. But compare it to the cost of a recall:- A single Listeria recall can cost $10M-$50M

- A FDA 483 inspection violation can shut you down for weeks

- A damaged brand reputation? Priceless

Bottom Line: It’s Not About Compliance. It’s About Control.

Environmental monitoring isn’t about passing an audit. It’s about knowing your facility inside out. It’s about catching the problem before the customer does. It’s about having data, not guesses. If you’re not doing this right, you’re gambling. The numbers don’t lie: 87% of foodborne outbreaks from environmental sources could’ve been prevented. That’s not a small number. That’s your plant. Start with your zones. Train your team. Use ATP for daily checks. Use swabs for proof. Tie your data together. Don’t wait for an inspection to find out you’re behind. Control isn’t expensive. Not doing it is.What is the main goal of environmental monitoring in manufacturing?

The main goal is to detect and prevent contamination before it reaches the product. It’s not about reacting to problems-it’s about identifying where contamination could come from-like air, water, surfaces, or equipment-and stopping it before it causes harm or a recall.

How often should Zone 1 surfaces be tested for contamination?

Zone 1 surfaces, which are in direct contact with food or pharmaceutical products, should be tested daily to weekly. In Ready-to-Eat food facilities, FDA regulations require weekly testing for Listeria monocytogenes. The frequency depends on risk, usage, and cleaning protocols.

What’s the difference between ATP testing and microbial swab testing?

ATP testing detects organic residue (like food, skin, or microbes) and gives results in seconds. It’s a cleanliness check. Microbial swab testing identifies specific pathogens like Listeria or Salmonella and takes 24-72 hours. ATP is for daily checks; swabs are for regulatory proof.

Why do Zone 3 and 4 areas matter if they’re not direct contact surfaces?

Contamination spreads. A dirty forklift tire (Zone 3) can track Listeria into a Zone 1 conveyor. A leaky pipe (Zone 4) can drip into a drain that backs up into production. Studies show over 60% of contamination events originate in these lower-risk zones. Monitoring them catches hidden threats.

What are the biggest mistakes companies make with environmental monitoring?

The top three: inconsistent zone classification, poor sampling technique (like using non-sterile swabs), and failing to connect data from ATP, microbiology, and allergen tests. Many facilities collect data but don’t analyze it together, missing patterns that could prevent outbreaks.

Is environmental monitoring required by law?

Yes. In the U.S., FDA’s Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and USDA’s Listeria Rule require environmental monitoring for high-risk food and pharmaceutical products. The EU’s Annex 1 mandates it for sterile drug manufacturing. Non-compliance can lead to shutdowns, fines, or product recalls.

Can small facilities afford proper environmental monitoring?

Yes, but it requires smart prioritization. Small facilities don’t need the same scale as big pharma. Focus on Zone 1 and 2, use ATP for daily checks, partner with a local lab for microbial testing, and train staff properly. The USDA found only 48% of small processors (<50 employees) are fully compliant-not because they can’t afford it, but because they don’t know where to start.

Lola Bchoudi

6 Dec, 2025

Environmental monitoring isn’t just about compliance-it’s about risk mitigation at the molecular level. Zone 1 swabs need to be standardized across facilities, otherwise you’re playing Russian roulette with pathogen transmission. ATP is a great first-pass tool, but it’s not a substitute for culture-based confirmation, especially when you’re dealing with Listeria biofilms in drain crevices. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on NGS is a game-changer; being able to identify strain-level contamination in under 24 hours means you can trace outbreaks back to their origin before the product even leaves the dock. If your lab is still using 72-hour incubation cycles, you’re already behind.

And don’t get me started on data silos. If your ATP readings, microbial logs, and allergen swabs aren’t feeding into a single dashboard with trend analytics, you’re flying blind. You need correlation, not just collection. Real-time dashboards that flag anomalies-like a spike in Zone 3 CFUs after a floor wash-are the difference between a near-miss and a recall.

Training is non-negotiable. I’ve seen techs use the same swab on Zone 1 and Zone 4 because they ‘didn’t want to waste supplies.’ That’s not cost-saving. That’s liability waiting to happen. 40 hours of hands-on training isn’t a suggestion-it’s the bare minimum. And quarterly refreshers? Mandatory. Compliance isn’t a checkbox. It’s a culture.

Small facilities can absolutely do this. Prioritize. Zone 1 and 2 first. Partner with a regional lab. Use ATP for daily sanitation verification. But don’t cut corners on sampling technique. The cost of a single recall dwarfs your entire annual monitoring budget. This isn’t an expense. It’s insurance.

And yes, AI is coming. But it won’t fix bad protocols. It’ll just make bad protocols faster. Solid foundation first. Then scale smart.

Bottom line: Control isn’t optional. It’s the only thing standing between your product and a headline that kills your brand.

Morgan Tait

7 Dec, 2025

They’re lying to you. All of them. The FDA? The USDA? The ‘experts’? They want you to think this is about safety. Nah. It’s about control. Who owns the data? Who controls the swabs? Who gets to say what’s ‘acceptable’? Big Pharma and the food conglomerates? They’re using environmental monitoring as a weapon to crush small players. You think $25k/year is expensive? Try paying for a third-party auditor who shows up with a 483 form because your Zone 3 mop bucket wasn’t ‘sanitized to their exact spec.’

ATP testing? That’s a placebo. It tells you there’s ‘organic residue’-but what if that’s just sweat from your crew? Or dust from the roof? They don’t care. They want you to panic, spend more, and outsource everything to their approved vendors. And don’t even get me started on ‘AI predictive modeling.’ That’s just corporate jargon for ‘we’re selling you a black box that tells you what we already decided.’

Real talk? If your facility’s clean enough to not make people sick, you’re fine. Stop over-engineering. Stop over-testing. Stop letting consultants sell you fear. I’ve worked in five plants. The ones with the most paperwork? The ones with the most recalls. Coincidence? I think not.

They want you to believe you need $50k software dashboards. Nah. You need good people, clean floors, and common sense. The rest? It’s a racket. And you’re the mark.

Darcie Streeter-Oxland

8 Dec, 2025

While the post presents a comprehensive overview of environmental monitoring protocols, several critical omissions warrant formal clarification. First, the implicit assumption that Zone 3 and 4 contamination events are primarily attributable to procedural failure neglects the role of architectural design-particularly ventilation gradients and pressure differentials, which are not addressed herein. Second, the assertion that ATP testing is merely a ‘quick check’ fails to acknowledge its non-quantitative nature and the significant inter-instrument variability documented in ISO 16140-6:2021. Third, the recommendation to integrate disparate data streams into a single dashboard presumes interoperability of legacy systems, many of which remain proprietary and non-API-enabled. Furthermore, the absence of any reference to GMP Annex 1’s requirement for real-time environmental data logging (specifically 2.12 and 2.13) renders the guidance incomplete. Finally, the statistical claim that ‘87% of foodborne outbreaks from environmental sources could have been prevented’ lacks citation or methodological transparency. Until these gaps are addressed, the utility of this framework remains questionable.

Taya Rtichsheva

10 Dec, 2025

Zone 3 is where the magic happens lmao who knew a forklift tire could be the real villain? 😅

Christian Landry

11 Dec, 2025

This is actually super helpful 😊 I work at a small nut butter shop and we’ve been kinda winging our swabs. Just started using ATP sticks daily and it’s crazy how much residue we’re picking up-like, way more than we thought. We’re gonna get our crew trained next month, maybe even get a cheap shared lab account for microbial tests. Thanks for breaking it down so clearly! 🙌

Katie Harrison

12 Dec, 2025

Thank you for this detailed, well-structured overview. It is imperative to emphasize that environmental monitoring is not merely a regulatory obligation, but an ethical imperative. The data presented-particularly the 87% preventable outbreak statistic-underscores a moral responsibility to consumers, many of whom are immunocompromised, elderly, or young children. The fragmentation of data systems, as noted, is not simply an operational inefficiency; it is a failure of stewardship. Moreover, the assertion that small facilities can implement these practices through prioritization is not only accurate, but profoundly empowering. It is not the scale of investment that determines safety, but the rigor of intent. I urge all stakeholders to treat this not as a cost center, but as a cornerstone of public trust. The consequences of negligence are not abstract. They are real. They are human. And they are entirely avoidable.