When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s not luck. It’s the result of strict science and regulatory rules enforced by the FDA. For generic drug makers, proving this isn’t optional - it’s the entire foundation of getting approval. The key? Bioequivalence studies.

What Bioequivalence Really Means

Bioequivalence isn’t about looking the same or having the same name. It’s about proving that your generic drug delivers the same active ingredient to your bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the original brand drug. The FDA is the U.S. government agency responsible for ensuring that drugs are safe, effective, and consistent. And for generics, that means matching the Reference Listed Drug (RLD) - the brand-name drug that’s already on the market.The FDA’s definition is precise: bioequivalence means no significant difference in how quickly and how much of the drug enters your system. If the generic doesn’t do this, it could be too weak to work - or too strong and cause side effects. That’s why the FDA doesn’t accept claims like “similar” or “almost the same.” It demands hard data.

The Two Rules: Pharmaceutical Equivalence and Bioequivalence

Before a generic can even start testing, it must meet two basic criteria. First, pharmaceutical equivalence. That means the generic must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (pill, injection, etc.), and route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the brand drug. Simple enough? Not quite. Even small differences in inactive ingredients - like fillers or coatings - can change how the drug breaks down in your body.That’s where bioequivalence comes in. The FDA requires manufacturers to run clinical studies showing that the generic performs like the RLD in real people. These are called pharmacokinetic studies. They track how the drug moves through the body over time, using blood samples to measure two key numbers: AUC and Cmax.

- AUC (Area Under the Curve) tells you how much of the drug gets absorbed overall.

- Cmax (Maximum Concentration) shows how fast the drug reaches its peak level in the blood.

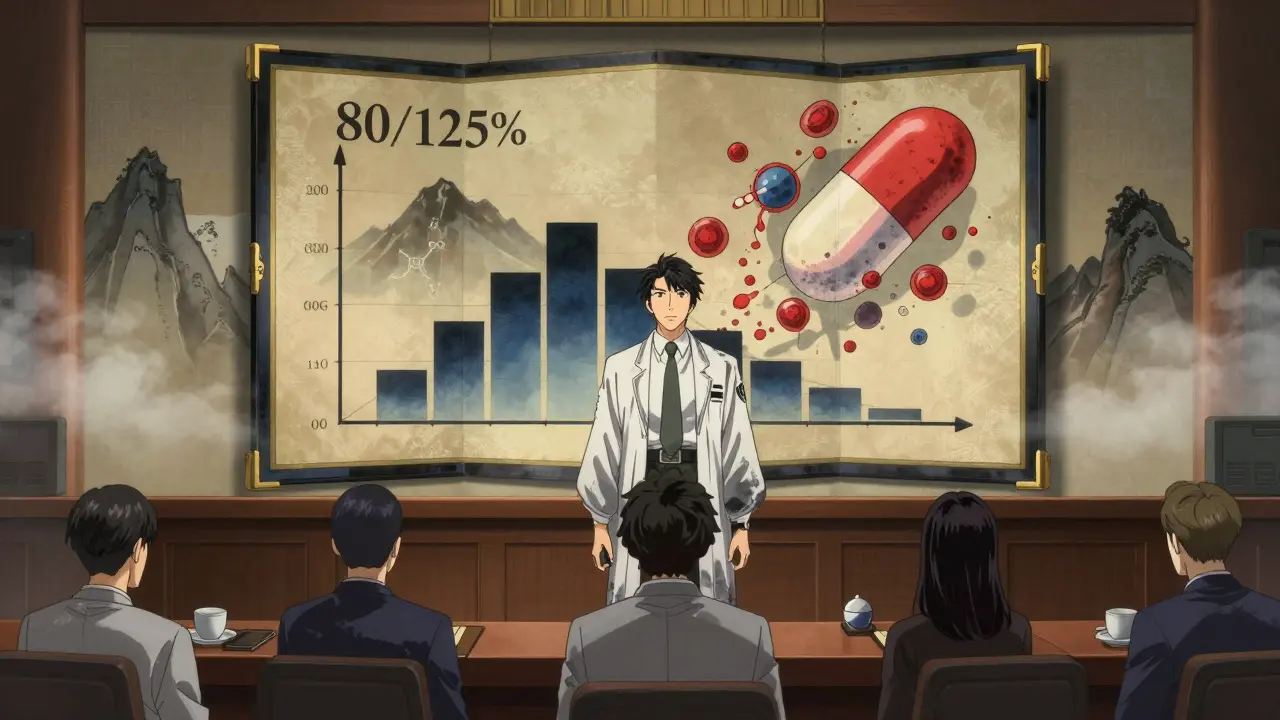

For the generic to be approved, the 90% confidence interval for both AUC and Cmax - when comparing the generic to the brand - must fall between 80% and 125%. This is known as the 80/125 rule. It’s been the gold standard since 1992 and hasn’t changed. Why this range? Because studies show that if two drugs fall within these limits, they’re just as likely to produce the same therapeutic effect. It’s not about being identical - it’s about being therapeutically equivalent.

Who Gets Tested? And How?

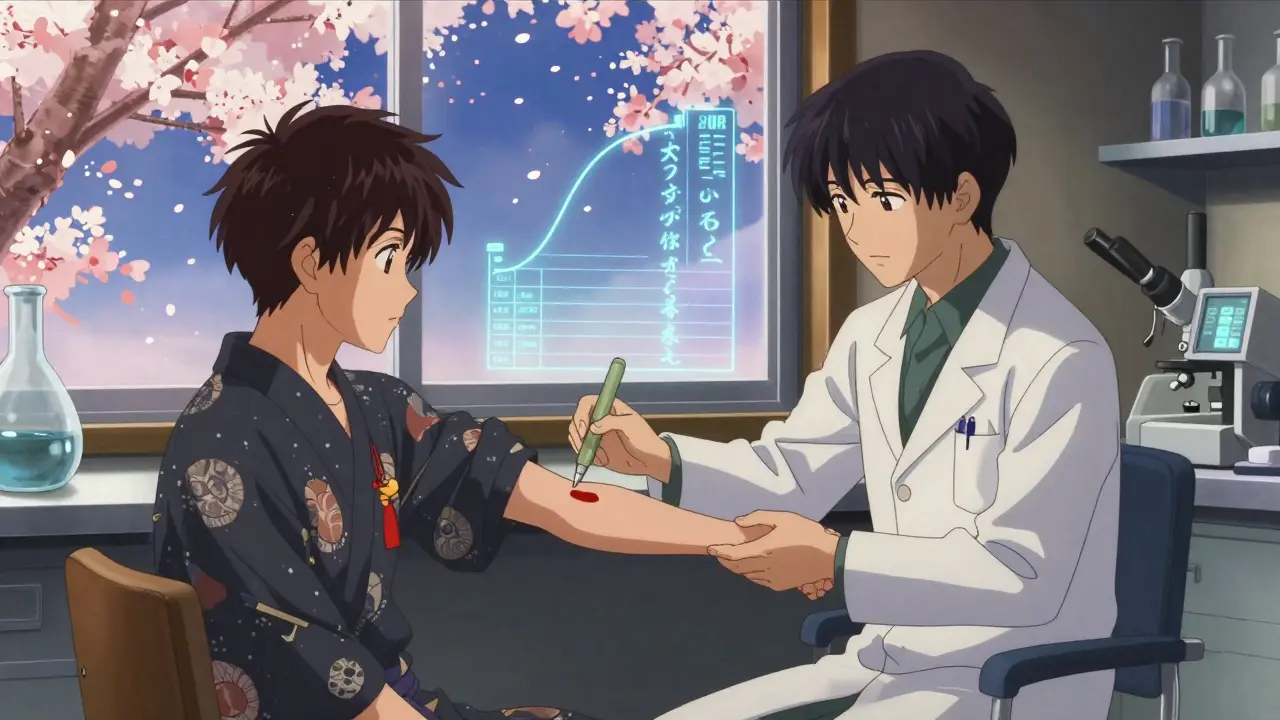

Most bioequivalence studies involve 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These aren’t patients - they’re people with no major health conditions who can safely take the drug under controlled conditions. The study is usually done in two parts: one where participants take the generic drug on an empty stomach, and another where they take the brand drug. Then they switch. This is called a crossover design, and it helps eliminate individual differences between people.For drugs that are affected by food - like some antibiotics or cholesterol meds - a second study is required under fed conditions. That’s because eating can change how well your body absorbs the drug. The FDA doesn’t assume it works the same way. It requires proof.

All studies must follow strict rules. Labs need to be certified under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), and samples must be handled, stored, and analyzed exactly as documented. Even small mistakes - like a blood sample sitting too long before testing - can invalidate the whole study.

When Can You Skip the Human Study? (Biowaivers)

Not every generic needs a full clinical trial. The FDA allows biowaivers - exceptions where manufacturers can prove bioequivalence without testing in people. These are granted only for specific cases where the science is clear enough to predict performance without human data.For example:

- Topical creams or ointments meant to work on the skin (not absorbed into the blood) can use in vitro tests to show the drug releases at the same rate.

- Oral solutions with the exact same ingredients as an approved brand may qualify if their pH and viscosity match.

- Inhalers and eye drops with identical formulations can sometimes skip human trials too.

The criteria for a biowaiver follow the Q1-Q2-Q3 rule: same active ingredient (Q1), same dosage form and concentration (Q2), and same physical-chemical properties (Q3). If all three match, and the drug isn’t absorbed systemically, the FDA may accept lab tests instead of human studies. This saves time and money - sometimes cutting development by a year or more.

Special Cases: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some drugs are extremely sensitive. Even tiny changes in blood levels can cause serious harm. These are called narrow therapeutic index drugs (NTIDs). Examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid disorders), and phenytoin (for seizures).For these, the FDA doesn’t accept the standard 80/125 rule. Instead, it requires a tighter range: 90% to 111%. This means the generic must be nearly identical in how it behaves in the body. The margin for error is razor-thin. Manufacturers of NTID generics face much higher scrutiny. One study showed that nearly half of all rejected ANDAs for these drugs were due to bioequivalence issues.

Why So Many Generic Applications Get Rejected

Despite the clear rules, the FDA approves only about 43% of generic applications on the first try. Why? Because most submissions miss the mark - not because the science is flawed, but because the paperwork isn’t perfect.Common mistakes:

- Using outdated study designs that don’t meet current guidance

- Not following the Product-Specific Guidance (PSG) for that exact drug

- Poor analytical methods for measuring drug levels in blood

- Incomplete documentation of sample handling or lab procedures

Companies that follow the FDA’s Product-Specific Guidance for their drug have a 68% first-time approval rate. Those who don’t? Only 29%. The PSGs are detailed documents - over 2,100 of them - that spell out exactly what data the FDA expects for each drug. Ignoring them is like trying to build a house without blueprints.

What’s Changing in 2026?

The FDA isn’t standing still. New tools are being added to the toolkit. One big shift is the use of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. This computer-based method simulates how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemistry and biology. For complex drugs - like inhalers or topical products - PBPK models can reduce the need for multiple human studies.Also, the FDA is pushing for more local manufacturing. Under its Domestic Generic Drug Manufacturing Pilot Program, companies that produce the active ingredient and run bioequivalence studies in the U.S. get faster reviews. This is partly in response to supply chain risks exposed during the pandemic.

And for topical products - a major area of concern - the FDA is developing new in vitro models that can predict skin absorption without human testing. Draft guidance for 45 complex product types is expected by mid-2024.

Why This Matters to You

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they cost only 23% of what brand drugs do. That’s billions saved every year. Behind every cheap pill is a rigorous, expensive, and highly regulated process. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards aren’t red tape - they’re the reason you can trust a $5 generic as much as a $50 brand.If you’re a patient, you can be confident that your generic works. If you’re a manufacturer, the path is clear: follow the science, stick to the guidance, and don’t cut corners. The FDA doesn’t just approve drugs - it ensures safety, one blood sample at a time.

What happens if a generic drug fails bioequivalence testing?

If a generic drug fails to meet the FDA’s bioequivalence criteria, the application is rejected. The manufacturer must either redesign the formulation, conduct new studies, or submit additional data. Many companies go through multiple rounds of testing before approval. There’s no shortcut - the FDA will not approve a product that doesn’t meet the 80/125 rule (or 90/111 for NTIDs).

Can a generic drug be approved without any human testing?

Yes, but only in specific cases. The FDA allows biowaivers for certain products like topical creams, eye drops, and oral solutions if they match the reference drug exactly in ingredients, concentration, and physical properties. These waivers rely on in vitro testing instead of human trials. But for most oral pills and injectables, human studies are required.

Why does the FDA use 80% to 125% as the bioequivalence range?

This range is based on decades of clinical data showing that drugs falling within these limits produce the same therapeutic effect in most patients. The 80/125 rule isn’t arbitrary - it reflects the natural variability seen even between different batches of the same brand drug. If two products stay within this range, differences in effect are considered clinically insignificant.

Are bioequivalence studies the same in Europe and the U.S.?

Mostly yes. The FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have aligned their standards through the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH). Both require the 80/125 range for most drugs and use similar study designs. However, there are minor differences in how they handle highly variable drugs or complex formulations. Overall, 87% of bioequivalence requirements are now harmonized between the two agencies.

How long do bioequivalence studies take to complete?

A typical bioequivalence study takes 3 to 6 months from planning to final report. This includes recruiting volunteers, conducting dosing sessions, collecting blood samples, analyzing data, and writing the report. But the entire ANDA process - including FDA review - usually takes 14 to 18 months from submission to approval. The bioequivalence study is often the longest and most expensive part.

Do all generic drugs need to be tested in healthy volunteers?

No. For drugs that are unsafe to give to healthy people - such as chemotherapy agents or certain antibiotics - the FDA may allow studies in the target patient population. These are more complex and expensive, but they’re necessary when testing in healthy volunteers isn’t ethical or feasible.

What’s the cost of a bioequivalence study?

A single bioequivalence study typically costs between $500,000 and $2 million, depending on the drug’s complexity, the number of volunteers, and the analytical methods used. For drugs requiring multiple studies (fasting and fed, for example), costs can double. This is why many manufacturers seek biowaivers or use PBPK modeling to reduce testing needs.

Jennifer Glass

3 Jan, 2026

Really appreciate how clearly this breaks down the science behind generics. I’ve always assumed they were just cheap copies, but learning about the 80/125 rule and how much rigor goes into each study changed my whole perspective. It’s not magic-it’s math, biology, and regulation working together.

Akshaya Gandra _ Student - EastCaryMS

3 Jan, 2026

so like… if i take a generic adderall and it dont work same as brand, is it just bad batch or did the company cut corners??

Jacob Milano

5 Jan, 2026

Man, I used to think generics were sketchy until I saw my grandma switch from $200 brand-name heart meds to $8 generics and still live to 92. The FDA’s got your back even when you don’t realize it. These studies? They’re the unsung heroes of affordable healthcare.

en Max

6 Jan, 2026

It is imperative to underscore that the 90% confidence interval for AUC and Cmax, constrained within the 80%–125% bioequivalence range, is not merely a statistical convention-it is a pharmacokinetic benchmark validated by decades of clinical outcomes data. Deviations beyond this threshold are associated with clinically significant variations in therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles, particularly in polypharmacy contexts.

Angie Rehe

7 Jan, 2026

Let’s be real-this whole system is a joke. Companies game the system with ‘biowaivers’ for drugs that should NEVER skip human trials. And don’t get me started on how the FDA lets some generics through with sloppy documentation just because they’re ‘cost-effective.’ Patients are guinea pigs for corporate profit.

saurabh singh

8 Jan, 2026

bro in india we got generics that cost 1/10th of usa price and they work just fine. i had my cousin on generic warfarin for 3 years, INR stable as hell. the science is solid, dont let fear-mongers scare you. also, FDA rules are global now, so its not just us playing by the same book.

Abhishek Mondal

9 Jan, 2026

Actually, the 80-125% range is outdated! It was based on 1980s data and doesn’t account for modern pharmacogenomics. Some patients metabolize drugs 5x faster-so even if a generic falls within FDA limits, it could still be ineffective for them. The FDA is clinging to a myth. We need personalized bioequivalence thresholds… and they know it.

Aaron Mercado

11 Jan, 2026

WHY DO WE EVEN TRUST THE FDA?? They approved a generic for levothyroxine last year that caused 17 hospitalizations-AND STILL LET IT STAY ON THE SHELF!! This isn’t science-it’s corporate lobbying dressed up as regulation. People are DYING because some lab technician forgot to calibrate a machine!!

Peyton Feuer

13 Jan, 2026

Interesting read. I never thought about how food affects absorption-makes sense though. My cousin’s cholesterol med only works if she takes it with dinner. Guess that’s why they do the fed studies. Kinda wild that something so small can make or break approval.

Jennifer Glass

13 Jan, 2026

That’s actually a great point about food interactions. I read somewhere that some antibiotics like doxycycline can’t be taken with dairy because calcium binds to it. That’s why the fed/fasting studies matter so much-it’s not just about the pill, it’s about how your whole body interacts with it.